Background

Arizona – and particularly the Phoenix metro market – is now an expensive place to live. The current inflation crisis has accelerated a longer-run trend in the rapid appreciation of cost of living here relative to other major metro areas. For nearly three years, home prices in Phoenix have been rising faster than anywhere else in the country. At the same time, however, shelter inflation – measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics as a combination of owners imputed rent and renters market rent – has

lagged the US average and on a relative basis (compared to the U.S.) Phoenix is a more affordable city in which to rent today than 4 years ago. This disparity suggests CPI has yet to fully ‘catch up’ to true housing costs here.

Key Findings

- During the pandemic, domestic net migration to Arizona peaked at nearly 110,000 new movers in 2020 – a 68% increase since 2017 and the highest rate ever recorded for Arizona.

- That year, the state added 43,000 new housing units and issued permits to build 57,000 more – a remarkable feat given the pandemic and associated restrictions elsewhere but insufficient to keep pace with unprecedented growth.

- To keep pace with population growth and increase housing supply to the pre-pandemic lows of 2.25 people/unit, Arizona needs to add 206,000 new housing units by 2023 relative to 2020; based on permitting data, CSI estimates we will only fall about 11,500 units short of this level, suggesting the current home price crisis goes beyond a simple “home building shortfall”.

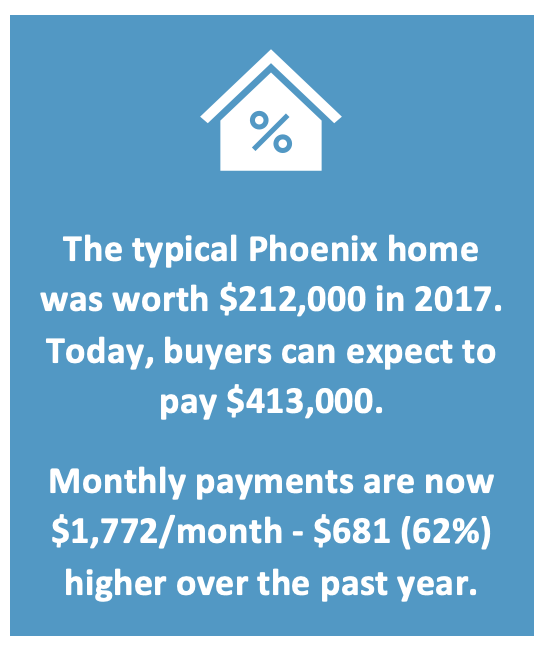

- The typical home in Phoenix now costs $413,000 and a typical mortgage payment at current rates is $1,772/month – up $681 (62%) in just the past year.

While interest rates are rising, 30-year mortgage rates remain low on an historical basis, which in turn alleviates some of the pressure rising prices are putting on the housing market. At the same time, however, this availability of “easy money” is likely contributing to rapid prices increases, and the prospect of rapidly rising interest rates (up 61% in the first 4 months of 2022 alone) in the face of historically high prices risks creating a perfect storm of buyer misery in the state’s housing market. CSI has developed the ‘home buyer misery index’ to track this trend – a normalized index of buyer costs that has averaged 100 over the past thirty years but could surpass 200 (effective costs double long-run averages) this year.

Housing as a Capital Asset

Generally, capital assets are tangible property that are likely to remain in the possession of the owner for an extended period (often perpetuity or the useful life of the asset), and that provide productive return. Housing provides shelter services to the owner – either as a business, if the property is rented out, or directly, if the property is owner-occupied - and therefore is an investment and not consumption. And since the housing provides a perpetual claim on this rental income stream, it can be resold to future investors, often at higher than purchase price.

Demand for housing – the asset – has clearly outpaced supply in Phoenix. Some of these supply constraints are real: the supply of land in the urban core is fixed and largely developed. Others are nationally driven: lender regulations that make it more difficult to obtain financing and rising interest rates tilt the asset markets in favor of professional investors, who are more likely to be cash buyers. According to an analysis by Redfin[i], nearly a third of Phoenix home sales are to cash buyers. Still others are local: land-use restrictions that make dividing existing parcels difficult or limit the density of development of those parcels favor incumbent owners over new entrants and distort the market quality of housing (leading to an over-supply of relatively more expensive single-family homes on larger lots). This is occurring even as demand – fueled by large in-migration since the pandemic – has risen rapidly.

As a result, housing prices in Phoenix are growing at their fastest pace ever, and price increases are highest in the lower-tier stock. Prices for an entry-level home in the Phoenix metro area have risen 77% since 2019 – versus 68% for Phoenix homes overall and a 40% rate for the United States.

This raises another key point: housing is a stock, not a flow. Any new units add to the total supply of housing in a market regardless of grade, and in-market movers from existing to new homes provides a key opportunity for first-time buyers to acquire existing single-family homes in the resale market. Regulations which restrict new development (for example, by requiring a certain proportion of new housing have below-market rents) reduce the willingness of existing owners to move, which in turn reduces opportunities for first-time buyers.

Historical evidence suggests a way to control the price of housingis to grow the housing stock more quickly than population. With a 1–3 year lag, if policymakers can support the development of new units of any quality housing price inflation should moderate somewhat. During periods of sustained housing market underproduction, price elevations follow. However, other factors – low interest rates and money supplies rising faster than economic growth – are likely dominant but outside the influence of state and local policy levers. While the supply of housing has failed to keep up with population growth recently (rising from a low of 2.25 people/unit in 2011 to over 2.30 in 2020), housing prices have become untethered recently from this metric, and CSI’s projections of rapid home construction based on building permits have this number coming back down by 2023. Further, a gradual decline in housing per capita over ten years is difficult to reconcile with a sudden acceleration in home prices over the last 18-24 months.

Nonetheless, CSI has heard anecdotally that labor and material shortages may be disrupting the historical relationship between building permits and housing unit growth. To the extent this is true, CSI may be overestimating new construction in Arizona, and the true supply problem may be larger than contemplated here.

Finally, we note that markets – including for housing – are sensitive to both prices, and the cost of money. When money is cheap, prices tend to be higher, but a market remains relatively accessible (consider the market for higher education and the abundance of federal loan money). Correspondingly, a rising cost of money should lead to falling prices, maintaining equilibrium. However, the rare combination of both high costs of money and high prices can create particularly miserable conditions for buyers – the prospect of which in housing prompted CSI to create a “home buyers misery index” of normalized summed mortgage rates and home prices. Note by this measure, even as home prices in Phoenix have risen more than 44% over their prior peak, the “misery index” has increased only 26% over its prior peak – buttressed by relatively lower 30-year mortgage rates today than in 2006. Still, conditions in housing now are more difficult for buyers than ever before, and rapidly rising interest rates are likely to outpace any possible relief in prices, further reducing market accessibility.

According to Zillow, the value of a typical Phoenix home was $413,000 in March – versus $212,000 just five years earlier. At prevailing rates, a typical homebuyer can expect to pay $1,772/month to buy a home today, an increase of $681 (62%) over the past year. If interest rates increase to 8% by the end of the year – even if home price appreciation slows to just 8% over the next 12 months – typical monthly homeownership costs would rise to $2,573 and the buyers ‘misery index’ would reach 215 (nearly 40% above its prior peak and more than double its 30-year average of about 100).

Rental of Housing Services as Consumption

As discussed, housing units are capital assets – while the rental of housing services provides needed shelter consumption. To measure costs and inflation on shelter consumption the Bureau of Labor Statistics relies on surveys of both owners and renters – while renters are asked to report their actual rental costs, owners are asked to report how much they think they could charge to rent their homes. This is import given that nearly a third of measured consumer prices consist of the cost of the shelter, and three-fourths of that relies on owner-reported expected rents, this creates interesting issues with the official measures of inflation: while over long time horizons market and owner-equivalent rents move together, generally, gaps can appear between the two which can have implications for measured consumer price inflation (particularly in environments where prices are changing rapidly).

Phoenix is such a market. Interestingly, even in the face of rapidly appreciating home prices (the fastest measured increases in the United States), rental prices are relatively more affordable in Phoenix today than they were five years ago. Specifically, while rental prices as measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics have increased 7% in Phoenix over the past year (and 5% in the United States as a whole), effective shelter costs here were only about 98% of the U.S. level in March – versus about 100% five years ago and higher than the nation in mid-2020.

To the extent shelter inflation lags home prices – as suggested by a Federal Reserve Bank study[ii] – this could portend continued high CPI inflation reads here and in other inland cities, as rents (especially owner-reported rents) continue to catch up to asset values. This phenomenon could be further exasperated if rising prices for owner-occupied housing push up demand for rental housing, putting additional pressure on rents and CPI inflation. These risks are again somewhat offset by the apparently rapid pace of new construction expected in Arizona through 2023, based on CSI’s internal projections using building permit data.

© 2022 Common Sense Institute

[i] Redfin News, Share of Homes Bought With all Cash Hits 30% for First Time Since 2014 (2021)

[ii] Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Recent Owner’s Equivalent Rent Inflation Is Probably Not a Blip (2014)