This research aims to review the history and evolution of our traditional public school system; investigate the concerns and examine the potential disparities that exist with respect to Black, Brown, and special needs students; and lastly review alternative learning models, including ESAs and outcomes for Black, Brown, and special needs students who utilize their school choice options.

The history of the traditional public school system traces back to the establishment of the Prussian model of education in the 18th century. The Prussian model, developed by the Kingdom of Prussia (modern-day Germany), served as the foundation for the development of traditional public education systems around the world, including the United States.

The Prussian model of education was based on the principles of compulsory education, standardized curriculum, and centralized control.[iv] It aimed to create a disciplined and compliant constituency, with a focus on instilling values of loyalty, compliance, and conformity to authority. The model emphasized the role of the state in providing public instruction as a means of social control, national unity, and economic development.

In the early 19th century, Horace Mann, an American education reformer, became inspired by the Prussian model and advocated for its implementation in the United States. Mann believed that a standardized, centralized public instruction system would help create a literate and moral constituency, ensuring social stability and economic progress.

As a result, traditional public schools in the United States adopted elements of the Prussian model. They became compulsory, free, and accessible to all children, regardless of social status or economic background. The curriculum became standardized, focusing on subjects such as reading, writing, arithmetic, and moral education. Traditional public schools were seen as a means of social mobility and equal opportunity, providing a foundation for a democratic constituency.

However, the adoption of the Prussian model in traditional public schools also had its problems. The promotion of conformity stifled individuality, which neglected the diverse needs and talents of students. The model also perpetuated social inequalities, as many low-income and marginalized communities had limited access to quality traditional public education and resources.

The traditional public instruction model has evolved over time and has added various pedagogical approaches. While the Prussian model serves as a conforming foundation, these changing approaches have introduced new risks and exacerbated potential systemic problems. For example, the changing focus from math, literacy and science to include more social and alternative subjects has combined with the conformity-focused District school model to quickly result in a system that today does arguably worse at educating its students – especially nonwhite students – than ever before.[v]

Now we turn our attention to the creation of Arizona’s traditional public instruction system and examine the use of the Prussian Model in our state's K-12 grade traditional public education system. Understanding the historical context of traditional public schools and the adoption of the Prussian Model in Arizona is essential for analyzing the current state of education in the state.

History of Arizona Traditional K-12 Grade Public Schools

Traditional public schools in Arizona have a long history dating back to the late 19th century. Initially, education in the state was provided through a combination of private schools, religious institutions, and informal home-based instruction. However, as Arizona transitioned from a territory to a state, the need for a more formal and standardized system of public instruction became evident. This led to the establishment of the first traditional public school districts and the development of a statewide traditional public instruction system.

Influence of the Prussian Model in Arizona’s K-12 Grade Public School System

The Prussian Model, also known as the Prussian education system, heavily influenced the structure and organization of Arizona's K-12 grade traditional public instruction system. The Prussian Model emphasized compulsory education, standardized curriculum, and a hierarchical structure. It focused on discipline, compliance, and preparing students for their roles as compliant constituents.

In Arizona, the adoption of the Prussian Model can be traced back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries when the state was establishing its traditional public instruction system. Key elements of the Prussian Model, such as compulsory attendance laws, standardized curriculum, and the use of grades and grade levels, were incorporated into Arizona's educational framework. These elements aimed to create a uniform and efficient system of education that would prepare students for their roles in society.

Arizona’s initial traditional public instruction model has not gone without criticism especially with the hierarchical structure and standardized curriculum which has failed to consistently meet the diverse needs and interests of all students. As a result, there have been ongoing discussions and reforms in Arizona and other states to address these concerns and promote more student-centered and inclusive approaches to education.

The Evolution of Arizona’s K-12 Traditional Public Schools

Since the adoption of the Prussian model in the United States, traditional public schools have undergone significant evolution, incorporated new philosophies, new pedagogical approaches, and societal changes. This evolution has been driven by a growing understanding of the diverse needs of students, changing educational goals, and the recognition of the importance of individuality and creativity in the learning process.

One major shift in the evolution of traditional public schools from the Prussian model has been the move towards a more student-centered approach to education. In the early 20th century advocates supported a progressive education model that focused on active learning, hands-on experiences, and the development of critical thinking skills. This departure from the rigid structure of the Prussian model aimed to foster creativity, individuality, and a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

Another significant evolution has been the recognition of the importance of inclusivity and equal access to education, which while providing free education to all students, did not always address the needs of low-income and marginalized communities. Over time, traditional public schools have made efforts to address these disparities by implementing policies such as desegregation and inclusive education for students with disabilities. The goal has been to create a more equitable educational system that ensures every child has the opportunity to succeed.

Additionally, traditional public schools in the United States have embraced a more holistic approach to education, recognizing the importance of social and emotional development alongside academic achievement. This shift has led to the inclusion of programs and initiatives that promote mental health, character education, and social-emotional learning. The focus is on nurturing the whole child and providing a supportive environment that fosters well-rounded development.

Furthermore, the advancement of technology has greatly influenced the evolution of traditional public schools. With the advent of computers, the internet, and digital tools, schools have integrated technology into the learning process opening up opportunities for a more personalized learning experience for each student.

Advocates in Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public education space have recently argued for a more student-centered and experiential learning environment with a move away from the rigid Prussian Model.[vi] The efforts to ensure equitable access to education for all students, regardless of their race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic background have continued to influence the evolution of public schools in Arizona. The development of special education programs has continued to enhance supports for students with disabilities in Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public education space.

The adoption of standard based learning and the integration of technology into the classroom has also transformed not only the required content to be taught, but the way education is delivered and accessed in Arizona K-12 grade traditional public schools.

Integration of Traditional Public Schools

The integration of Black, Brown, and special needs students into Arizona K-12 grade traditional public schools marked a significant milestone in the initial pursuit of equal access to traditional public education. Prior to the Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v Board of Education decision in 1954, public schools in the United States were allowed to maintain separate schools for minority and other underprivileged children. While the law technically required the separate facilities to be of “equal” quality, the practical reality is that the schools were not.

However, the question remains: do traditional public schools truly serve all students considering this integration? While progress has been made, there are still challenges and disparities that need to be addressed to ensure equitable educational opportunities for all. After more than 50 years of integration, it is still true that many schools (and especially school districts) in Arizona are either majority-white or majority-nonwhite, often depending on their geographic location. And as recently as 2023, some Arizona school districts - like Tucson Unified – were still the subject of ongoing federal litigation and court-ordered desegregation.[vii]

Still, in general, students tend to go to schools with students who look like them[viii] even though the system itself tends to be relatively mixed[ix] – less than half of all American traditional public school students in 2022 were white.

One key issue is the persistence of racial and ethnic disparities within Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public schools. Despite the efforts to integrate schools, studies have shown that students of color continue to face disproportionately higher rates of disciplinary actions, lower academic achievement, and limited access to advanced coursework. These disparities highlight the need for ongoing efforts to address systemic biases, provide culturally responsive teaching, and promote inclusive classroom environments.

Furthermore, special needs students often face significant challenges within Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public school system. While laws such as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) aim to provide appropriate educational services, there are still gaps in meeting the needs of these students. Limited resources, inadequate support services, and the lack of trained personnel can hinder the traditional public educational experience for students with disabilities. It is crucial to ensure that these students receive the necessary accommodations and support to fully participate in and benefit from the traditional public educational environment.

Additionally, there are structural and socioeconomic issues that can make it more difficult for nonwhite and disabled students to escape their struggling public schools. These students often come from lower-income background. There school districts are disproportionately rural or in parts of urban areas that have limited private- and alternative-school options.

Over time traditional District public schools have increased the share of financial resources going to activities other than traditional K-12 instruction. Administrative and support service spending has surged.[x] And even classroom and instruction spending has been more about meeting administrative and standardized testing responsibilities versus focusing on whether our children are mastering the basics: reading, writing and arithmetic.

Outcomes of Integration for Black, Brown, and Special Needs Students:

The integration of Black, Brown, and special needs students into Arizona’s traditional K-12 grade public schools has had both positive and challenging outcomes. While the initial goal of integration was to promote equal access to education and foster inclusive learning environments, the reality is that the outcomes have varied across different contexts. It is important to examine these outcomes realistically to better understand the progress made and identify areas that require further attention.

Ideally, integration is the opportunity for students from diverse backgrounds to interact and learn from one another. Integration should promote cultural understanding, empathy, and appreciation for diversity. It should allow students to develop social skills and prepare them for the multicultural realities of the world for which we are preparing them to be productive citizens. Integration also has the potential to challenge stereotypes and reduce prejudice among students, fostering a more inclusive and tolerant society. Unfortunately, often in Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public schools many of our Black students and in particular Black students with special needs experience a very exclusive and intolerant traditional public school environment and therefore have not been afforded the inclusive and tolerant society integration promotes.

Integration has the potential for improved academic outcomes for all students. Again, sadly, many of our Black, Brown, and our students with special needs do not experience this theoretical academic benefit. Research has shown that diverse classrooms can enhance cognitive development and critical thinking skills. When students from different backgrounds come together, they bring unique perspectives and experiences, which can enrich classroom discussions and enhance learning outcomes for all. Integration should provide opportunities for teachers to implement culturally responsive teaching practices, which would improve engagement and academic achievement among marginalized students.

However, due to the disparities in educational outcomes between different racial and ethnic groups, as well as special needs students, integration alone does not guarantee equity in education. It requires addressing systemic biases, providing targeted support for marginalized students, and ensuring equal access to resources and opportunities.

One challenge is the disproportionate disciplinary actions faced by Black, Brown, and special needs students. Data suggests and studies have confirmed that these students are more likely to be suspended or expelled compared to their White peers.[xi] This highlights the need for schools to provide appropriate support services for educators and school administrators who may not have the cultural awareness and/or capacity to address the underlying issues a Black, Brown or special needs student may be facing, versus the resultant punitive disciplinary actions often experienced by these students.

Integration can be particularly challenging for special needs students as they require individualized support and accommodations. The availability of trained personnel specialized programs, and assistive technologies is crucial to ensure that these students can fully participate in the classroom and achieve their academic potential.

Efforts to continue to integrate Black, Brown, and special needs students in Arizona's K-12 grade traditional public schools require ongoing commitment, collaboration, necessary resources, and accountability to ensure these resources go to meet the specific needs of these student groups; and once accomplished could significantly maximize the potential benefits of integration for all students.

Academic History for Black, Brown, and Special Needs Students vs. White Students:

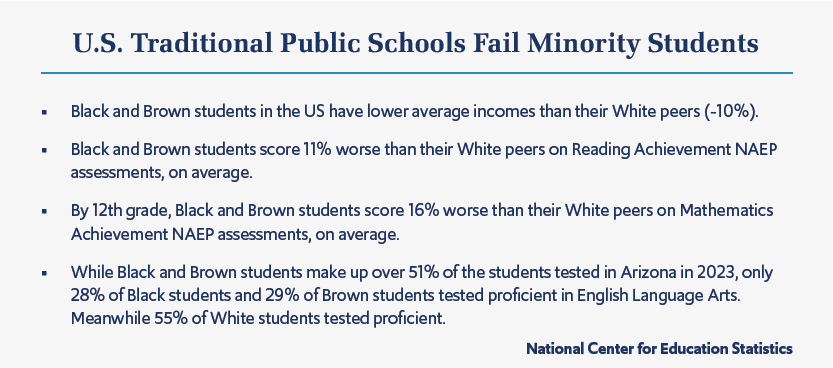

The academic history of Black, Brown, and special needs students compared to their White peers in Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public schools reveals significant disparities and inequities.[xii] While education should be a pathway to equal opportunities and success for all students, the reality is that these marginalized groups often face numerous challenges that hinder their academic achievement.

Research consistently shows that Black and Brown students, on average, perform lower academically compared to their White counterparts. This achievement gap can be attributed to various factors: systemic racism, inequitable access to resources, limited educational opportunities, disruption to their learning process due to frequent and lengthy suspensions/expulsions, and low academic expectations. Black and Brown students are more likely to attend underfunded schools with inadequate facilities, outdated textbooks/technology, experience low expectations by qualified teachers, a lack of qualified teachers, excessive absenteeism and disengagement. These disparities contribute to lower academic performance and increase educational inequities.

Special needs students and special needs students of color also face unique barriers in Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public schools. They often require individualized support and accommodations to meet their diverse learning needs. However, the resources and support services available to these students can be insufficient, inconsistent, and lack the needed care, resulting in a reduction in academic progress. Special needs students may experience difficulties in accessing learning platforms, specialized instruction, and assistive technologies that are designed to help them thrive academically. As a result, they often lag behind their non-disabled peers in terms of academic achievement.

The disproportionate disciplinary actions faced by Black, Brown, and special needs students further contribute to their academic struggles. Studies have shown that these students are more likely to be subjected to harsh disciplinary measures, such as suspensions and expulsions, compared to their white peers. This punitive approach to discipline disrupts their education and widens the achievement gap. It is crucial to implement practices that validate the humanity of each student, provide the adults in the space with the capacity to provide the necessary supports to address the underlying issues, rather than resorting to punitive measures.

The impact of these disparities in academic achievement extends beyond the school years. Lower academic performance can limit opportunities for higher education and future employment prospects, perpetuating a cycle of inequities. It is essential to address these disparities by creating safe and supportive learning environments for all children. Schools should strive to create learning environments that empower Black, Brown, and special needs students to reach their full academic potential.

Efforts to close the achievement gap require a multi-faceted approach. It is also important to engage parents, communities, and stakeholders in collaborative efforts to support and advocate for the academic success of marginalized students.

Disciplinary History for Black, Brown, and Special Needs Students vs. White Students:

The disciplinary history for Black, Brown, and special needs students compared to their White peers in Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public schools reveals a significant disparity in how disciplinary measures are applied. Research indicates that these marginalized groups are disproportionately subjected to harsh disciplinary actions, such as suspensions and expulsions at a higher rate, compared to their White counterparts. This disparity highlights a deeply rooted issue of systemic racism and discrimination within the traditional public education system.

Studies consistently show that Black and Brown students are more likely to be criminalized and disciplined for similar behaviors as their White peers, leading to higher rates of suspension and expulsion. This phenomenon is often referred to as the "school-to-prison pipeline," where punitive disciplinary measures disproportionately affect students of color and contribute to their involvement in the criminal justice system later in life. The over-policing and harsh disciplinary practices targeted at Black, Brown, and special needs students foster a cycle of inequitable treatment and significantly hinder the educational success of Black, Brown, and special needs students.

Research has demonstrated that racial biases and stereotypes have influenced disciplinary decisions, with Black and Brown students being seen as more threatening or disruptive compared to their White peers. These biased and stereotypical perceptions result in harsher disciplinary actions, further widening the achievement gap and limiting educational opportunities for many of our Black and Brown students.

Moreover, special needs students often face additional challenges in the disciplinary process. For example, in 2020-21, students with special needs made up 13% of the student population but received 27% of all suspensions and 15% of all expulsions. The lack of understanding and support for their unique needs can lead to misinterpretation and criminalization of their behaviors, resulting in disciplinary actions rather than providing appropriate accommodations or interventions. This punitive approach not only fails to address the underlying issues but also exacerbates the challenges faced by special needs students, significantly hindering their academic and social development.

Zero-tolerance policies, which enforce strict disciplinary measures for certain behaviors, have been criticized for disproportionately affecting Black, Brown, and special needs students. These policies often result in harsh punishments, such as suspension or expulsion, without considering the underlying factors contributing to the behavior. These underlying factors can be related to the following:

- Poverty with limited access to resources and opportunities.

- Housing instability, frequent moves, and unstable living environments.

- Homelessness and the toll that takes on the emotional well-being of children.

- Family dynamics including structure, support, parental involvement or lack of, domestic violence, community violence, exposure to violence, lack of mental health support and/or resources.

- Negative school climate, bullying, lack of supportive teachers, resources, access to counseling services, lack of individualized support for special needs.

- Unmet special needs.

- Stereotypes, stigmas, and insufficient understanding of cultural norms and behaviors.

- Failure to recognize and value diverse backgrounds.

Any one or a combination of these underlying factors can further exacerbate the disparities in disciplinary actions.

Disciplinary actions may also be influenced by cultural differences and misunderstandings. Behaviors that are perceived as disruptive or disrespectful by school staff may be rooted in cultural practices, gender differences, or communication styles. For example, while boys are about half of total enrollment, they receive three-fourths of suspensions and expulsions. It is important for educators to receive training and support to recognize and address these cultural differences appropriately.

Students who are subjected to frequent suspensions and expulsions are more likely to fall behind academically, experience disengagement from school, have an increased likelihood of dropping out and find themselves as potential candidates for the school-to-prison pipeline. The disruption to their education can have long-term negative effects on their future prospects and influence cycles of poverty and inequities.

Addressing the disciplinary disparities requires a multi-faceted approach. Schools must implement practices that focus on repairing harm, fostering healthy mindsets and relationships, and promoting the humanity of all students. Educators and administrators should receive training on how to humanize and effectively interact with culturally diverse students and their families, the importance of equitable disciplinary practices and how to create safe and supportive learning environments for all students. Additionally, it is crucial to develop and implement policies that promote alternatives to suspension and expulsion, such as self-management techniques, peer-to-peer conflict resolution, and above all fostering genuine relationships with their student’s parents/guardians. Relationships with families give educators insight on what is going on in their students’ personal lives, which aids in decisions regarding discipline and potential barriers to learning.

Furthermore, collaboration with parents, communities, and stakeholders is essential to creating a more inclusive and supportive school environment. Engaging in ongoing dialogue, fostering partnerships, and actively involving families in the decision-making process can help address disciplinary issues in a more comprehensive and equitable manner.

Traditional public school-to-prison-pipeline

The school-to-prison pipeline refers to the alarming trend where students, particularly those from marginalized backgrounds such as Black, Brown, and special needs students, are funneled from Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public schools into the criminal justice system. Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public schools play a significant role in fueling this pipeline, as punitive disciplinary practices and a lack of support contribute to the over-criminalization and exclusion of these students.[xiii]

One of the key contributing factors is the implementation of zero-tolerance policies in many traditional public schools. These policies mandate severe disciplinary measures, such as suspensions and expulsions, for even minor infractions. However, these policies disproportionately target Black, Brown, and special needs students, resulting in their exclusion from the educational environment.

Research consistently shows that Black and Brown students are more likely to be disciplined, suspended, or expelled compared to their White peers for similar behaviors. For example, in the 2017-18 school year, Black students made up 5% of students enrollment in Arizona but received 11% of all suspensions. A similar story is true with other ethnicities as well; Asian, Native American, or Pacific Islander students make up 11% of the traditional public school students in Arizona, but in 2017-18 they made up 19% of suspensions and 16% of expulsions. This disparity is rooted in systemic racism, biases, and stereotypes where students of color are often perceived as more threatening or disruptive. As a result, these students are more likely to have repeated encounters with disciplinary actions, leading to disengagement from school and increased involvement with the criminal justice system.

Special needs students also face significant challenges within the school-to-prison pipeline. Many Arizona K-12 grade traditional public schools lack the necessary resources, accommodations, and support systems to meet the unique needs of these students. Instead of providing appropriate interventions and assistance, these students are often subjected to punitive disciplinary measures that do not address the underlying issues. This punitive approach further marginalizes special needs students and increases their likelihood of entering the criminal justice system.

Furthermore, the presence of police officers or school resource officers (SROs) in Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public schools contributes to the criminalization of Black, Brown, and special needs students. While the intention behind having SROs is to ensure safety, their presence often leads to increased arrests, citations, and criminal charges for minor infractions of Black, Brown, and special needs students. These students are disproportionately targeted by these disciplinary measures, further perpetuating their involvement in the criminal justice system.

The consequences of the school-to-prison pipeline are extremely traumatic and have long term consequences. Students who experience exclusionary disciplinary practices are more likely to have lower academic achievement, increased dropout rates, and limited future opportunities. The labeling and stigmatization associated with being involved in the criminal justice system also hinders their ability to reintegrate into society and lead productive lives.

To address Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public schools’ role in the school-to-prison pipeline, it is crucial to implement alternative disciplinary approaches that promote alternatives to suspension and expulsion, such as self-management techniques, peer-to-peer conflict resolution and above all fostering genuine relationships with their student’s parents/guardians. Relationships with families give educators insight on what is going on in their students’ personal lives, which aids in decisions regarding discipline and potential barriers to learning. How would we accomplish getting parents and teachers to communicate better? I strongly believe the following practices would certainly aid in this endeavor:

- Regular check-ins via phone, text, email, or in-person.

- Create opportunities for informal conversations to build rapport.

- Validate parents’ experiences and perspectives regarding education.

- Demonstration of understanding of cultural backgrounds and practices.

- Parent involvement in the development of IEPs and/or behavioral management plans.

- Set shared expectations and outcomes for student success.

- Encouragement to share feedback, insights on how a student is doing and any concerns about the student’s academic or overall well-being.

- Recognize potential language barriers, colloquialisms, or jargon and mindfully pave the way for clear communication.

- Create a welcoming school culture for parents to participate in day-to-day activities and feel empowered to advocate for the needs of their children free from bias or judgement.

- Promote mutual respect and a sense of belonging.

Another essential step is to reconsider the presence of police officers or SROs in schools. Many SROs lack the training to disseminate between a crime being committed or a child having behavior issues. SROs often times approach disciplinary actions with the mindset of apprehending a suspect and/or arresting a criminal. Instead of relying on punitive measures, schools should focus on creating safe and supportive learning environments that prioritize building trusting relationships with students and families. Again, when educators humanize the students and the families they serve, this fosters a safe and supportive learning environment, which in turn reduces the need for Black, Brown, and special needs students to be apprehensive about their safety and well-being. Trust, love, and acceptance will foster a safe and supportive learning environment for Black, Brown and special needs students in Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public schools. It is also vital for Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public schools to establish partnerships with community organizations, stakeholders, and school families to further address the underlying social and economic factors Black, Brown, and special needs students face on a daily basis.

There are alternatives available to traditional schools that can accomplish the combined goals of ensuring safe learning environments, without treating students with behavioral problems like criminals. For example, juvenile probation officers may have the training and experience needed to better fulfill these kinds of roles. In general, though, private and non-traditional school environments function well without these officers – and ESAs enable impacted students to get to those places.

The Need for Alternate Learning Environments for Black, Brown, and Special Needs Students.

Black, Brown, and special needs students have long faced significant challenges within the Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public school system as previously discussed. These challenges manifest in treatment disparities, as well as academic underperformance, leading to a pressing need for alternative learning environments that prioritize their unique needs and experiences.

One of the key issues faced by these students in Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public schools is the lack of understanding the individual needs of these students. Many educational institutions fail to provide an inclusive curriculum that reflects the diverse backgrounds and experiences of Black, Brown, and special needs students. This lack of representation, cultural relevance, humanization, learning supports and academic expectations can lead to disengagement, alienation, embarrassment, humiliation, and a significant hindrance to their academic achievement.

Additionally, Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public schools often lack the necessary resources and support systems to address the specific challenges faced by these students. Special needs students, for example, require individualized education plans (IEPs) and accommodations to ensure their academic success. However, due to a lack of specialized services, limited resources, as well as at times an inadequate distribution of resources these students may not receive the tailored support they need within Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public schools.

Furthermore, the disciplinary practices in Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public schools disproportionately target Black, Brown, and special needs students, which can lead to increased suspensions, expulsions, and even involvement with the criminal justice system. This punitive approach fails to address the underlying issues contributing to behavioral challenges and further exacerbates academic underperformance.

Alternative learning environments can empower Black, Brown, and special needs students by fostering their voice and agency in the educational process. These environments provide opportunities for student-led initiatives, leadership development, and involvement in decision-making. By valuing student perspectives and experiences, alternative learning environments can promote a sense of ownership and empowerment, leading to improved academic engagement and performance.

Given the systemic barriers, disparities and lack of student voice and agency in Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public schools, alternative learning environments emerge as a crucial solution to better support the educational needs of Black, Brown, and special needs students.

Arizona’s Alternative Learning Environment Models

Arizona offers a wide range of school choice options, including homeschooling, public charter schools, private schools, Montessori schools, online schools, as well as the newly formed microschools and learning pod models. This section of the research paper examines the impact of these various school choice options on the academics, safety, and support for Black, Brown, and special needs students.

Homeschooling has gained popularity as a school choice option in Arizona. It allows parents or guardians to take on the role of the primary educator for their children. Homeschooling can provide a flexible and individualized educational experience for Black, Brown, and special needs students. Parents can tailor the curriculum to meet their child's specific needs and incorporate culturally relevant materials and teaching approaches. This personalized approach can lead to improved academic outcomes and a greater sense of cultural identity and empowerment for these students.

Public charter schools are another school choice option in Arizona that offers an alternative to traditional public schools. These schools operate independently and have more autonomy in their curriculum and teaching methods. Public charter schools often focus on specific educational approaches or themes, such as STEM or the arts. For Black, Brown, and special needs students, public charter schools can provide specialized programs and support services that address their unique needs. This targeted support can contribute to improved academic performance and a sense of belonging for these students.

Private schools in Arizona offer an alternative to public education, often with smaller class sizes and specialized programs. Private schools may have the resources to provide additional support services and accommodations for Black, Brown, and special needs students. However, it is important to note that private schools may have admission requirements and tuition fees, which can limit access for some families. The impact of private schools on the academics, safety and support for these student populations can vary depending on the specific school and its resources.

Montessori schools follow the educational philosophy developed by Maria Montessori, emphasizing self-directed learning and hands-on experiences. Montessori education can benefit Black, Brown, and special needs students by promoting independence, self-regulation, and a holistic approach to learning. Montessori schools often have blended age classrooms, allowing students to learn from and support each other. This inclusive environment can foster social-emotional development and academic growth for these students.

Online schools, also known as virtual schools, provide education through online platforms and virtual classrooms. Online schools offer flexibility in terms of scheduling and location, making them accessible to Black, Brown, and special needs students who may face barriers in traditional public school settings. However, online learning may pose challenges for certain students, such as those who require hands-on support or struggle with self-directed learning. The impact of online schools on academics, safety, and support for these student populations should be carefully evaluated, taking into consideration the individual needs and circumstances of each student.

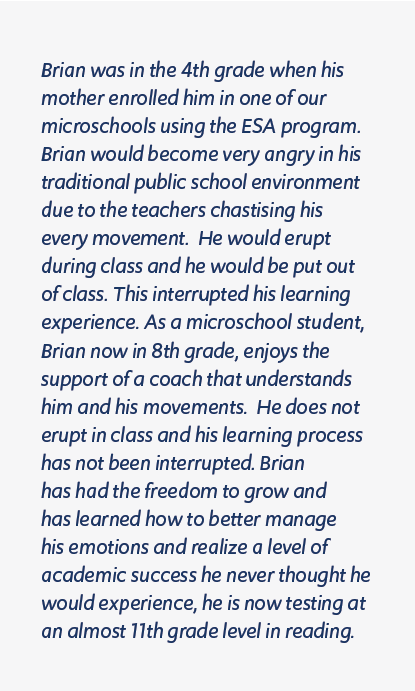

In recent years, microschools and learning pods have emerged as alternative educational models, particularly in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.[xiv] microschools are small-scale schools that often operate within non-traditional settings, while learning pods bring together a small group of students for shared learning experiences. These models provide personalized attention, tailored instruction, and a close-knit community for Black, Brown, and special needs students. The smaller learning environments and individualized support can contribute to improved academic outcomes and a sense of belonging and support for these students.

Regarding safety and support, it is important to consider the unique challenges that Black, Brown, and special needs students may face in different school choice options. Schools and educational models must prioritize creating safe and supportive learning environments for all students, addressing issues of discrimination, bullying, and providing appropriate support services. The impact on safety and support can vary across school choice options, and it is essential to ensure that the specific needs of these student populations are met in each educational setting.

In conclusion, Arizona's K-12 grade various school choice options, including homeschooling, public charter schools, private schools, Montessori schools, online schools, microschools, and learning pods, can have a significant impact on the academics, safety and support for Black, Brown, and special needs students. Each option offers unique benefits and considerations, and it is crucial to evaluate the specific needs and circumstances of each student when making educational decisions. Schools and educational models should strive to provide safe and supportive learning environments that promote academic achievement, cultural identity, and overall well-being for these student populations.

ESAs and their potential for positive educational outcomes for all students, specifically Black, Brown, and special needs students:

This section of the research paper examines the potential of Empowerment Scholarship Accounts (ESAs) in Arizona to generate positive educational outcomes for Black, Brown, and special needs students. ESAs are a school choice program that provides eligible students with public funds to be used for various educational expenses, including private school tuition, tutoring, therapy services, and educational materials. The focus will be on the impact of ESAs on academics, safety, and supportive needs for these student populations.

Academics

ESAs offer Black, Brown, and special needs students the opportunity to access educational settings that better meet their unique academic needs. With the flexibility to use ESA funds for private school tuition, students can choose schools that provide specialized programs, smaller class sizes, and tailored instruction. This can lead to improved academic outcomes for these students, as they receive individualized attention and support that may not be available in Arizona’s K-12 grade traditional public schools. By having the option to select schools that align with their learning styles and needs, students may experience enhanced engagement, motivation, and academic success.

Safety

Safety is a crucial consideration for all students, and ESAs have the potential to address safety concerns for Black, Brown, and special needs students. In some cases, students may face challenges such as bullying, discrimination, or lack of support in their current Arizona K-12 grade traditional public school environment. ESAs provide families with the ability to choose educational settings that prioritize safety and create safe and supportive learning environments. By selecting schools that have strong anti-bullying policies, diverse and inclusive communities, and a commitment to meeting the needs of all students, students may experience increased feelings of safety and well-being.

Supportive Needs

ESAs can also have a positive impact on the supportive needs of Black, Brown, and special needs students. With the ability to utilize ESA funds for tutoring, therapy services, and specialized educational materials, families can access additional resources that support their child's specific needs. This targeted support can address academic challenges, provide necessary therapies or interventions, and enhance overall educational experiences. By having the flexibility to choose and have direct access to these supportive services, students may experience improved academic progress, social-emotional development, and overall well-being.

However, it is important to note that the success of ESAs in generating positive educational outcomes for Black, Brown, and special needs students is not guaranteed. There are potential challenges and considerations that need to be taken into account. For example, the availability of suitable educational options and the quality of services may vary across different areas and schools.

In 2021, the BMF microschool campuses operated by Black Mothers Forum members had a total enrollment of 13 children. Since opening we have operated two campuses and one home-based microschool we have served 148 students; 100% of our students are on an ESA program. I am confident that in the absence of an ESA, many – even most – of these students would not be able to remain in private schooling. Their history of disciplinary and academic problems would make it difficult or even impossible for them to be effectively served by their traditional district public school system. Many would drop out without ever finishing a K-12 grade program; and the sad reality is, some would end up in one of our state’s prisons.

In conclusion, Empowerment Scholarship Accounts (ESAs) have the potential to create positive educational outcomes for Black, Brown, and special needs students in terms of academics, safety, and supportive needs. By providing families with the flexibility to choose educational settings that better align with their child's needs, ESAs can lead to improved academic performance, increased feelings of safety and well-being, and access to necessary supportive services. However, further research and evaluation are needed to assess the effectiveness and equity of ESAs in meeting the needs of all students and ensuring the availability of high-quality educational options.

The Bottom Line

It is clear that traditional public schools do not serve all students. Black, Brown and special needs students struggle to achieve at anywhere near the levels of their White and traditionally-abled peers. In recent years, male students have been increasingly left behind their female counterparts by the traditional district public school system.

The growing demand for home- and micro-schooling options provide novel alternatives for students most failed by traditional educational systems. However, there is a significant cost in terms of time and money for parents trying to utilize these alternative models.

The Empowerment Scholarship Account program uniquely enables participation by these families. My experience with our microschool families confirms this with certainty. Though the population may be small –students in our microschools, and approximately 70,000 K-12 grade students enrolled in ESAs – are composed of students who stand to lose everything without this public support.