The total economic cost of crime in Oregon in 2023 was an estimated $968.8 million, impacting individuals, communities, and public systems well beyond the immediate harm to victims. This includes an estimated 479,317 reported incidents spanning violent and property offenses. Among these, 124,184 were violent crimes—such as murder, rape, robbery, and assault—and 348,757 were property crimes, including motor vehicle theft, burglary, and larceny. However, official figures only scratch the surface of the true crime landscape. National data from the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) reveal that many crimes go unreported, particularly violent offenses, indicating the actual number of crimes committed in Oregon is likely far higher.

The NCVS provides reporting rates for different crime types, measured as the number of crimes reported per 1,000 individuals. For example, only 22.5 incidents of rape or sexual assault per 1,000 individuals are reported, compared to 1.7 robberies and 2.6 assaults. Property crimes exhibit similarly low reporting rates, with 9 burglaries, 6.1 motor vehicle thefts, and 83.1 thefts reported per 1,000 individuals. When these reporting rates are factored in, the gap between reported crimes (captured by the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting system) and actual criminal activity becomes apparent, highlighting the significant underreporting of crime in Oregon.

To estimate the economic cost of crime, this analysis employs the methodology developed by Miller et al., as published in the Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis. This framework calculates both tangible and intangible costs associated with crime, providing a comprehensive view of its economic burden. Tangible costs include direct monetary losses such as medical expenses, lost wages, property damage, and public service expenditures on law enforcement, adjudication, and corrections. Intangible costs, meanwhile, capture the profound psychological and emotional toll on victims, represented through quality-of-life losses derived from jury award data. The Miller framework offers a rigorous approach to valuing these costs by combining real economic losses with the broader societal impacts of victimization.

For violent crimes, the costs are particularly high. A single murder, for example, imposes an estimated economic burden of $9.1 million. This staggering figure is driven primarily by quality-of-life losses, which are valued at $5.15 million per incident. These losses account for the emotional suffering of victims’ families and the societal impact of losing a life. Additionally, lost productivity—reflecting the future earnings and household contributions of the victim—adds another $1.8 million per murder. Medical costs, public service expenditures for law enforcement and adjudication, and other tangible expenses contribute to the remainder of the total cost. This methodology captures not only the immediate costs of a murder but also its lifetime consequences, ensuring a comprehensive estimate.

Rape, while less costly than murder, imposes an average economic burden of $289,928 per incident, with over 70% of this figure attributable to intangible quality-of-life losses. The remaining costs include medical and mental health expenses, as well as lost productivity for victims. Assaults, which are among the most frequently reported violent crimes in Oregon, carry an average cost of $50,072 per incident, while robberies impose a cost of $29,215 per incident. These figures highlight the profound financial and social impacts of violent crimes, even when their frequency is lower than property crimes.

Property crimes, though less severe on a per-incident basis, represent a significant aggregate burden due to their high frequency. In 2023, Oregon recorded 348,757 incidents of larceny or theft, making it the most common crime category in the state. Each theft carries an average cost of $1,600, which includes property loss and public service expenditures. Similarly, motor vehicle thefts, with an average cost of $11,015 per incident, and burglaries, at $3,206 per incident, contribute heavily to the state’s overall economic burden of crime.

The disparity between reported and unreported crimes further complicates the picture. For instance, while the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) data capture crimes brought to the attention of law enforcement, the NCVS indicates that a substantial share of criminal activity goes unreported. Violent crimes are especially underreported, with many victims citing fear of retaliation or distrust in the justice system. When adjusted for underreporting, the total number of crimes committed in Oregon likely far exceeds the reported figure of 479,317 incidents, with violent crimes accounting for a significant portion of the unreported activity.

One of the key insights from the Miller et al. framework is the disproportionate economic impact of violent crimes relative to their frequency. While violent crimes represented only about 25.9% of all reported incidents in Oregon, they account for the vast majority of total costs due to their severity and long-term consequences. Intangible quality-of-life losses dominate the cost estimates, comprising over 75% of the total costs for violent crimes. By contrast, property crimes, though more frequent, impose a smaller economic burden per incident but remain significant due to their volume.

The total economic cost of crime in Oregon for 2023, estimated at $14.9 billion, underscores a substantial financial burden. Violent crimes, while accounting for only 25.91% of all reported incidents, are responsible for 64.73% of these costs, translating to approximately $9.65 billion. This disproportion highlights the severe repercussions that violent offenses have on societal and economic structures.

Murder ranks as the most financially draining crime with 245 occurrences costing the state a staggering $2.2 billion. This cost is primarily composed of quality-of-life losses, reflective of the profound societal and emotional toll inflicted by such tragedies. The economic impact of rape and sexual assault is similarly severe, cumulating to $2.1 billion, with the overwhelming majority stemming from the intangible losses borne by the victims and the community.

Assault, as the most frequently reported violent crime, generates significant economic implications totaling $3.8 billion. This highlights the broad and sustained impact these offenses have on Oregon’s public systems and the overall well-being of its residents. The collective economic impact of property crimes, though individually less severe per incident, still contributes a significant burden due to their prevalence. Larceny and theft, the most common offenses, result in costs totaling $558 million primarily due to the high volume of incidents.

Motor vehicle theft and burglary add further strain, with costs amounting to $254 million and $121 million respectively, demonstrating the tangible impacts of these crimes on individual victims and public resources. The financial ramifications of fraud also stand out, with total losses surpassing $2.1 billion, encapsulating both direct and systemic financial impacts on businesses and governmental functions. Vandalism, although less critical, still poses substantial costs of $171 million primarily due to property damage and subsequent public service expenditures.

These figures illustrate the extensive financial repercussions of crime across Oregon, driven predominantly by violent offenses that, despite their lower frequency relative to property crimes, impose a disproportionately higher economic burden.

City Level Perspective on Crime

The Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program compiles data from different law enforcement agencies, including city police departments, county sheriffs, and state agencies. City police report crimes occurring within municipal boundaries, while county or state law enforcement agencies report offenses that take place in unincorporated areas or outside city limits.

Portland, with a rate of 66 index crimes per 1,000 residents, has the highest index crime rate among Oregon cities, reflecting the challenges of policing densely populated urban centers. However, it is important to note that Portland’s reported crime data only includes incidents handled by the Portland Police Bureau. Crimes reported by other agencies, such as the Multnomah County Sheriff’s Office or campus police at institutions like Portland State University (PSU) and Oregon State University (OSU), are not included in these figures. In practice, many crimes occur near jurisdictional boundaries, and law enforcement agencies in those areas—including county sheriffs and state police—may also report crimes within the Portland metro area. This overlap can make it difficult to precisely attribute crimes to specific jurisdictions, particularly in urban areas where city borders are not always clearly defined in practice.

As a result, the reported crime rate for Portland likely underestimates the true crime rate for the broader Portland metro area. This is in contrast to the statewide crime estimates for Oregon, which incorporate both police-reported and non-police-reported crimes using National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) data. The statewide approach offers a more comprehensive view of crime trends, whereas Portland’s data reflects only those crimes specifically reported to and handled by the city police.

Smaller cities like Coos Bay (63) and Seaside (60) also report notably high rates, which may be driven by localized factors such as economic challenges or tourism-related activity. Conversely, rural and suburban areas such as Banks, Columbia City, and Gervais report significantly lower rates at 5 crimes per 1,000 residents, highlighting the relative safety of less densely populated regions.

In 2023, Portland faced substantial costs from criminal activity, with the total economic burden reaching $52.1 million across all reported offenses. Violent crimes alone accounted for $22.9 million, reflecting the significant impact of these offenses on the city’s public safety and resources. On average, crime in Oregon consumed 5.19% of residents’ annual incomes, with violent crimes alone accounting for 3.34%. However, these figures represent only crimes reported by the Portland Police Bureau and do not account for additional incidents captured by other agencies within the metro area. This limitation underscores the need to interpret Portland’s crime data with caution, as the actual crime rate for the Portland metro area is likely higher than what is reflected in these numbers.

Among violent crimes:

- Murder resulted in the highest individual cost, with 83 reported cases incurring $15.4 million in total costs.

- Assault was the most prevalent violent crime, with 9,201 incidents contributing $49.5 million, highlighting the strain on healthcare, law enforcement, and judicial systems.

- Robbery accounted for 1,215 incidents, with a total cost of $2 million, while rape and sexual assault collectively added $361,135.

Property crimes also imposed a considerable economic toll:

- Larceny/Theft led the category with 23,738 reported cases, resulting in $24.5 million in costs.

- Motor Vehicle Theft, with 8,147 incidents, added another $7.2 million to the total.

- Other offenses, including burglary and arson, collectively contributed an additional $297,338.

Drug-related crimes, such as drug possession and sales, accounted for 486 incidents, with a total cost of $3 million. This underscores the intersection between substance abuse and broader criminal activity in the city.

Lesser-known but impactful crimes included vandalism, with 10,346 cases costing $300,034, and fraud, with 3,474 cases costing $316,134. These highlight the wide-reaching economic implications of non-violent crimes.

Overall, Portland’s crime landscape in 2023 reflects the significant financial and social challenges posed by both violent and non-violent offenses. The data underscores the need for targeted interventions to address the underlying causes of crime, including substance abuse and economic disparities. However, it is important to reiterate that the figures presented here are based on crimes reported by the Portland Police Bureau and do not account for incidents reported by other agencies operating within the broader metro area. As such, these numbers likely underestimate the true scope of crime in Portland, highlighting the limitations of relying solely on city-level reporting for comprehensive analysis.

Measure 110 and Drug Epidemic in Oregon

Between 2020 and 2022, Oregon experienced a significant rise in both drug-related deaths and violent crime. Overdose death rates surged from 17,336 per 100,000 people in 2020 to 22,614 per 100,000 people in 2023, representing a 28.9% increase. Violent crime rates followed a similar trajectory, rising from 259 incidents per 100,000 residents in 2020 to 322 per 100,000 residents in 2022, a 24.3% increase. These trends reflect the growing intersection of drug use and crime in the state, with overdose deaths serving as a proxy for the prevalence of drug use.

The implementation of Measure 110 in 2020 introduced a significant shift in Oregon's approach to drug policy. By decriminalizing possession of small amounts of drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine and reallocating cannabis tax revenues toward addiction treatment, the measure aimed to reduce incarceration rates and address systemic racial disparities in the criminal justice system. However, the policy faced immediate challenges. Most funds designated for addiction treatment and recovery programs were not distributed until August 2022, leaving a critical gap in resources during the measure's early implementation phase.

In parallel, the state witnessed dramatic increases in deaths related to synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, which rose from 393,181 in 2020 to 650,938 in 2023. Deaths involving psychostimulants with abuse potential, including methamphetamine, climbed from 161,550 in 2020 to 308,707 in 2023. These figures underscore the rapidly growing impact of synthetic drugs on Oregon’s communities. Synthetic opioid-related deaths rose sharply from 393,181 in 2020 to 650,938 in 2023, reflecting statewide trends. These increases strained public health and safety resources, as the visible impacts of drug addiction, including homelessness and drug-related crime, became increasingly apparent in urban centers.

Law enforcement agencies expressed concerns about adapting to Measure 110, particularly the lack of enforcement tools to address public drug use and its consequences. Critics argue that the policy, while well-intentioned, unintentionally encouraged open drug use and reduced accountability mechanisms for addressing addiction. These concerns, coupled with rising overdose and violent crime rates, prompted state lawmakers to revisit the policy in 2024. New legislation reintroduced criminal penalties for the possession of small amounts of certain drugs, while continuing to prioritize treatment over incarceration, reflecting an attempt to balance public health and safety.

Oregon's experience with Measure 110 highlights the complexities of addressing drug addiction and its societal impacts. While the policy succeeded in reducing some drug-related arrests and introduced a framework for addiction recovery, its implementation revealed significant challenges. The sharp rise in overdose deaths and violent crime during its rollout underscores the importance of balancing harm reduction strategies with effective resource allocation and enforcement policies. As Oregon continues to refine its approach, these data-driven insights provide valuable lessons for other states considering similar reforms.

The Cost of Drug-Related Crime in the United States

Drug use does not just contribute to public health crises; it also drives significant criminal activity, adding a substantial burden to society. Using data from the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) on offenses involving offender's suspected use of drugs and narcotics, it is possible to estimate the proportion of crimes where drug use played a role.

Based on NIBRS data, drugs were involved in 5.5% of murders, 3.2% of rapes, 2.3% of assaults, and 47.1% of drug possession or sales offenses in 2023. These figures underline the role of drugs not only in violent crimes but also in offenses like vandalism, fraud, and property crimes. While violent crimes remain a critical concern, property crimes and other offenses tied to drug activity further emphasize the wide-ranging impacts of substance abuse on communities.

Economic Costs of Drug-Related Crime

The financial impact of drug-related crimes is immense. In 2023, the total cost of crimes involving drugs in the United States was estimated at $968.8 million, with violent crimes accounting for approximately $333.8 million of this total. These costs reflect expenditures on law enforcement, legal processes, incarceration, healthcare, and lost productivity, as well as the broader societal toll of crime.

Violent crimes such as murder, rape, and assault are among the most expensive offenses:

- Murder: With a drug involvement rate of 5.5%, the total drug-related cost of murder was $122.6 million in 2023.

- Rape (No Child Sex Abuse): Drug-related costs were estimated at $66.2 million, with 3.2% of cases involving drugs.

- Assault: Accounting for $88.4 million in drug-related costs, assaults constituted the largest financial burden among violent crimes.

Beyond violent crimes, property and other offenses also contribute significantly:

- Drug Possession/Sales: With nearly half (47.1%) of these offenses linked to drugs, the cost reached $42.1 million.

- Fraud: Though fewer cases involved drugs (0.9%), the high cost per offense led to a total cost of $19.2 million.

- Vandalism: At a drug-related rate of 1.0%, vandalism cost an estimated $1.7 million.

The data reveals a disproportionate economic burden from offenses that involve drugs, even when their prevalence within a category is relatively low. For instance, while only 0.8% of larceny/theft cases involved drugs, the widespread nature of this offense resulted in total costs of $4.5 million. Similarly, drug-related motor vehicle thefts, at 0.6%, added $1.5 million to the economic toll.

CRIME IN OREGON – A BRIEF HISTORY

Oregon’s public safety landscape has seen profound transformations over the decades, characterized by rising crime rates through the 1960s and 70s, significant legislative reforms in the 1980s and 90s, and a steady decline in crime rates in subsequent years. These shifts can be better understood through the lens of index crimes, which serve as a standardized measure of public safety. Comprising violent offenses—murder, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault—and property crimes—burglary, larceny-theft, motor vehicle theft, and arson—index crimes provide a consistent framework for tracking criminal activity. As shown in the figure, Oregon’s index crime rate rose steadily for decades, peaking in the late 1980s before a significant decline following policy reforms.

The crime wave of the mid-20th century reflected national trends as urbanization, rising drug use, and social shifts contributed to sharp increases in both violent and property crimes. Property crimes such as burglary and theft dominated Oregon’s statistics, while violent offenses, although less frequent, also increased significantly. By the late 1980s, Oregon’s index crime rate had reached its highest point, underscoring the need for systemic reforms.

Oregon's public safety landscape has undergone significant transformations over the decades, marked by rising crime rates through the 1960s and 70s, legislative reforms in the 1980s and 90s, and a gradual decline in crime rates. These changes can be analysed through the lens of index crimes, a standardized category that includes violent offenses such as murder, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault, as well as property crimes like burglary, larceny-theft, motor vehicle theft, and arson. As shown in Figure X, Oregon’s index crime rate rose steadily over decades, peaking in the late 1980s before declining through the 1990s and stabilizing in more recent years.

The crime wave of the mid-20th century reflected broader national trends, with societal shifts, urbanization, and increased drug use contributing to sharp increases in both violent and property crimes. In Oregon, property crimes such as burglary and theft dominated, while violent crimes, although less frequent, also saw significant increases. By the late 1980s, Oregon’s index crime rate reached its peak, highlighting the need for systemic policy responses.

Legislative measures introduced during this period appear to align with shifts in these crime trends. For instance, the Sentencing Guidelines of 1989 standardized sentences for felony crimes, promoting consistency and proportionality in sentencing. These guidelines allocated prison resources for severe violent crimes while offering alternative sanctions, such as probation, for lower-level offenses. This structured framework aimed to manage Oregon’s criminal justice resources more effectively.

In 1994, Measure 11 introduced mandatory minimum sentences for 16 serious crimes, including murder, rape, and robbery, and required juveniles aged 15 and older charged with these crimes to be tried as adults. The timing of Measure 11 coincides with a notable decline in Oregon's violent crime rates, suggesting a potential relationship between stricter sentencing policies and reduced crime. However, multiple factors, including demographic shifts, economic conditions, and advances in policing during the 1990s, likely influenced the observed reduction.

As seen in Figure, the 1990s marked a turning point for Oregon's index crime rates, with declines observed in both violent crimes, such as aggravated assault and robbery, and property crimes, including burglary and motor vehicle theft. These patterns align with broader national trends during this period, suggesting that both local reforms and nationwide factors contributed to the reduction.

Despite these declines, property crimes have continued to present challenges, often linked to economic conditions and substance abuse. In response, Measure 57, passed in 2008, enhanced penalties for repeat

property offenders while introducing treatment-focused solutions for drug-related offenses. This measure reflects the evolving understanding of the relationship between substance abuse and crime, emphasizing the need for multifaceted approaches to crime prevention.

The Budgetary Cost of Crime in Oregon

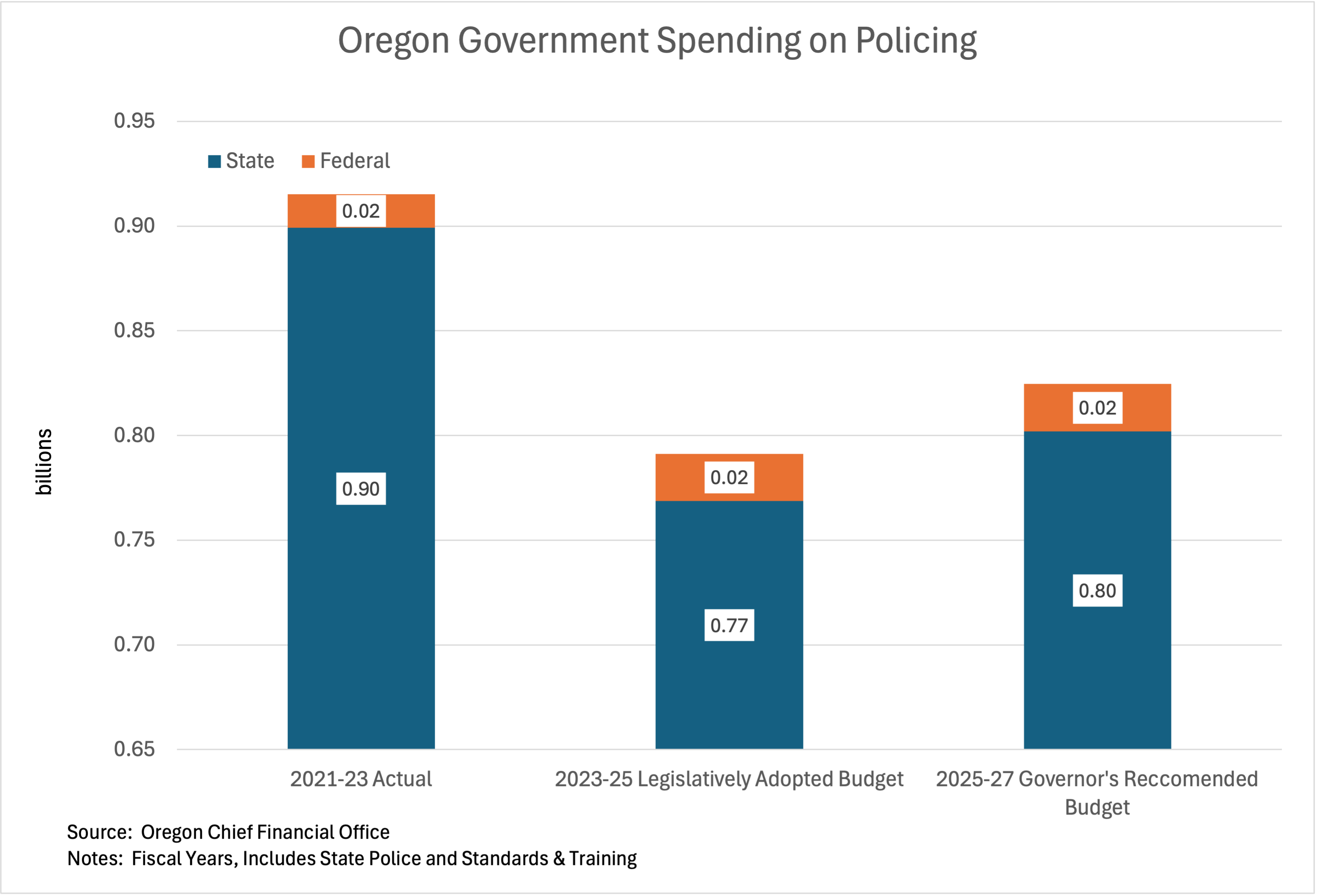

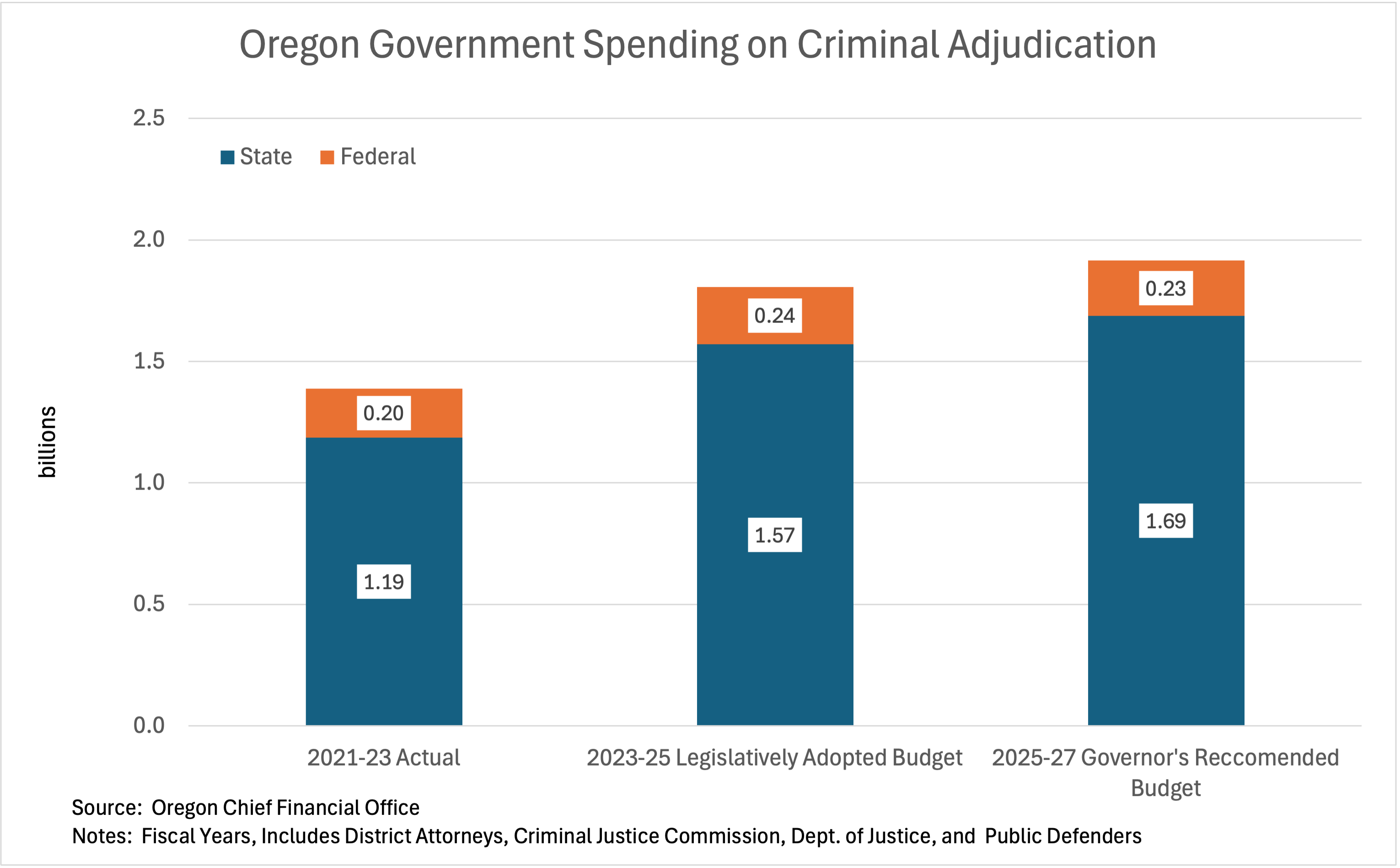

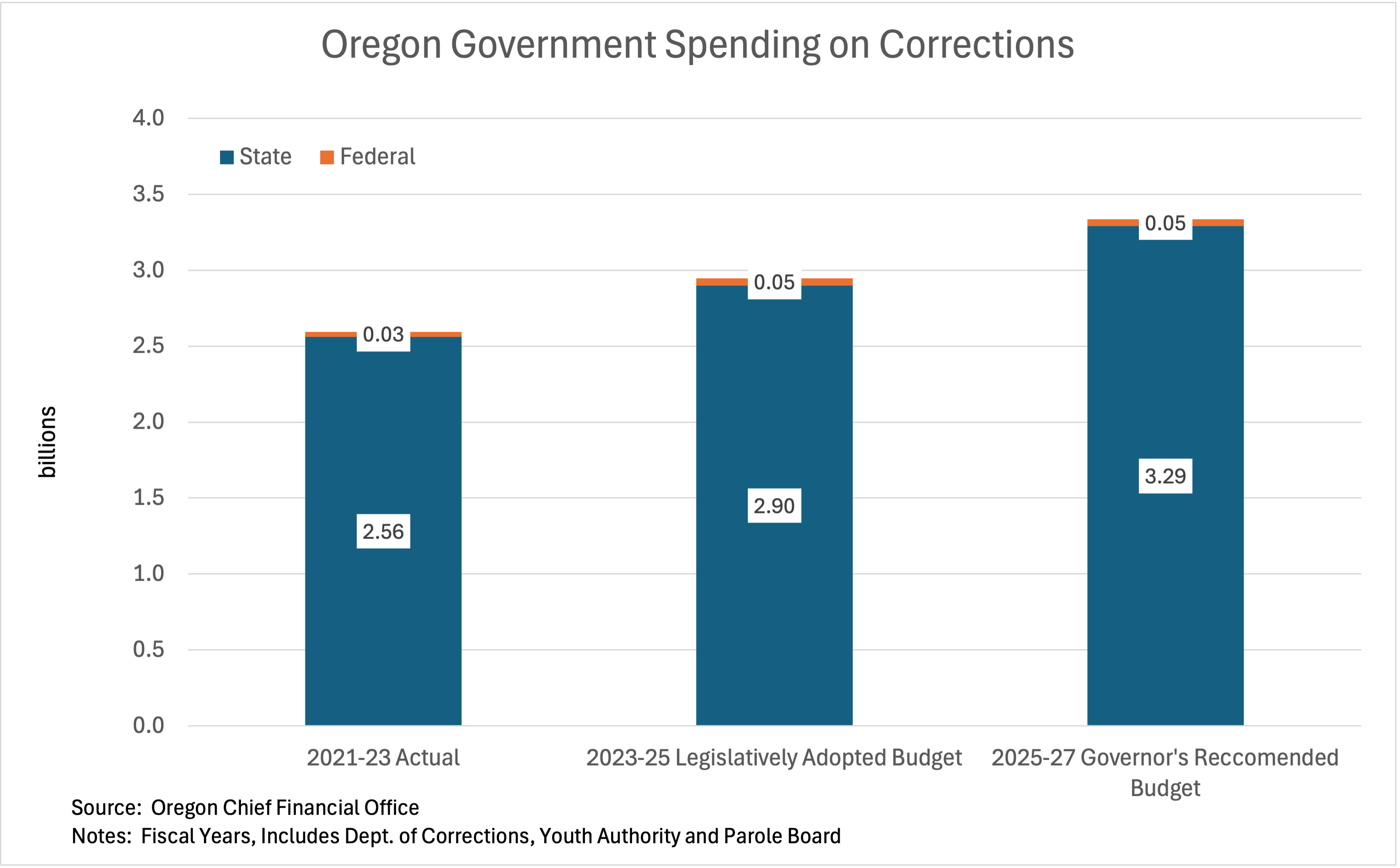

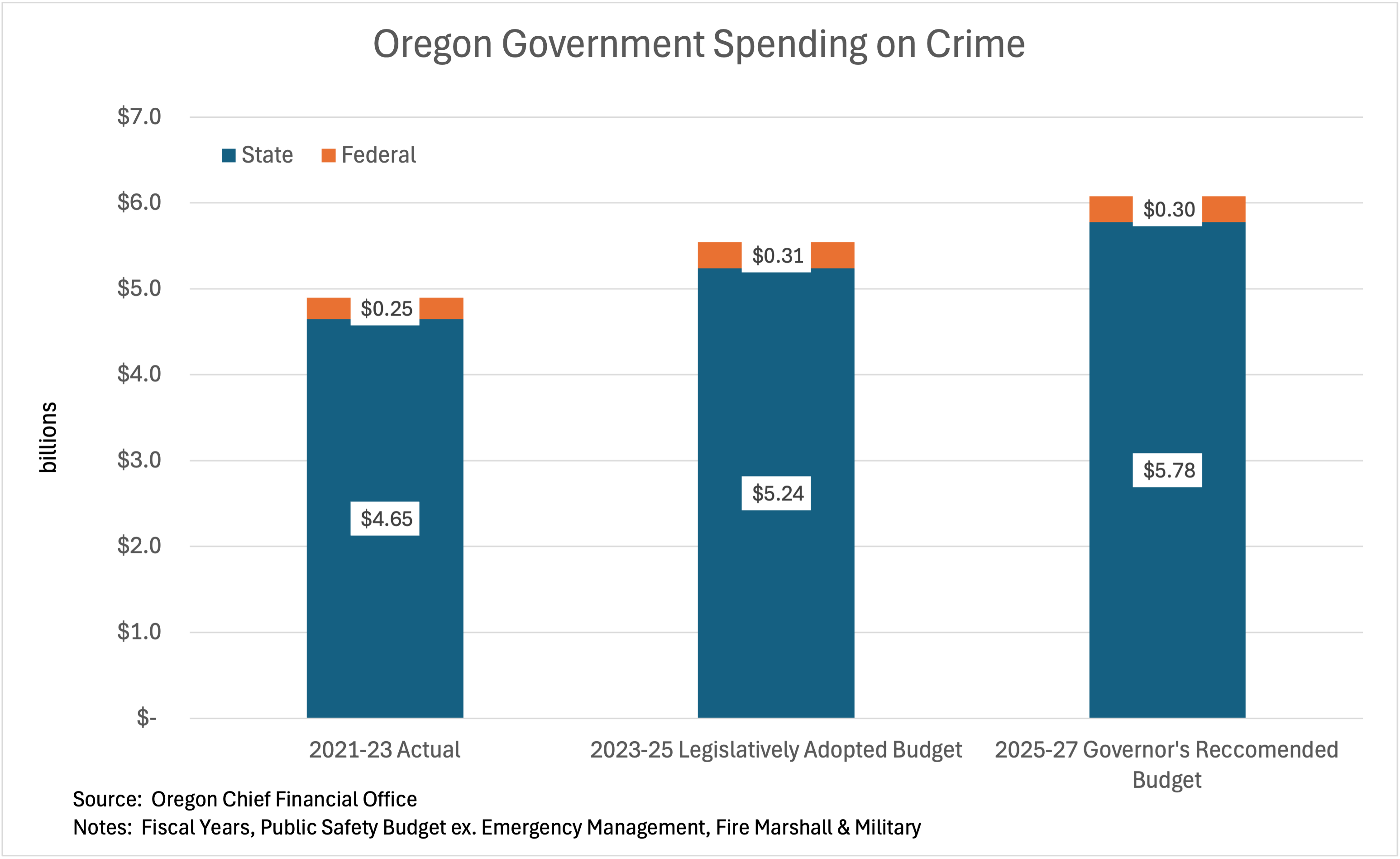

Budgetary pressures resulting from criminal activity stretch far beyond the costs of incarceration. State and federal spending on public safety in Oregon (excluding Military, Fire Marshall and Emergency Management) are proposed to amount to $6.1 billion in the Governor’s Recommended Budget. This would be more than triple the spending from a decade ago. Local governments also bear a large cost burden for police, courts and jails.

The Governor’s Recommended Budget calls for spending on criminal activity to rise by 9.6% over the next biennium, led by a 13.2% increase in the cost of corrections. Although the number of adults in custody has just begun to rebound from pandemic lows, costs per inmate are rising rapidly. An aging prison population has led to higher costs, particularly for healthcare services as incarcerated adults are entitled to a community standard of care. Incarcerated adults live longer on average than other Oregonians since they do not fall prey to auto accidents, overdoses, cirrhosis and the like. Costs for the youth population are not rising as quickly, since the population served is a function of the amount of funding provided by the legislature. The budget for state police has declined for technical reasons, as the Office of the Fire Marshall is no longer under their portfolio. Similarly, adjudication costs have increased somewhat as the Office of Public Defense Services has been moved to the executive branch.

Although the budgetary costs of crime are growing, they have not rebounded to pre-pandemic levels to the same extent as have measures of underlying criminal activity such as arrests or reported crimes. Given the level of index crimes caseloads for youth and adult correctional facilities and the courts would be expected to be higher. Coming out of the pandemic, it was assumed that this disconnect was the result of backlogs in the court system following shutdowns. However, now these backlogs have been cleared, suggesting that other factors are at play. One issue is that a smaller share of people charged with crimes are appearing for court dates. Also, there remains a significant shortage of public defenders in Oregon. Discretion on the part of judges and prosecutors is also clearly playing a role.

Crime Trends in Oregon: A Historical Perspective

Oregon’s crime rates have followed a long-term downward trajectory, consistent with national patterns over the past four decades. This decline can be attributed to demographic shifts, particularly the aging of the baby-boom generation, which reduced the proportion of young, high-risk individuals. However, this trend has stalled in recent years, and certain crime categories have seen sharp increases. Between 2010 and 2023, aggravated assault rose by 45%, and motor vehicle theft surged by 126%, reversing earlier progress and emphasizing the evolving nature of criminal activity in Oregon.

Oregon’s crime trends, measured through the lens of index crimes, highlight a story of dramatic increases, steady declines, and recent fluctuations. Index crimes encompass both violent crimes—murder, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault—and property crimes, including burglary, larceny-theft, and motor vehicle theft (MVT). Together, these categories provide a comprehensive view of the state’s public safety dynamics over the decades.

In 1960, Oregon’s index crime rate stood at 1,977.2 per 100,000 residents, with property crimes comprising over 96% of all offenses. Burglary, larceny-theft, and MVT accounted for the bulk of this figure, with larceny-theft alone contributing 1,371.2 per 100,000 residents. Violent crimes, while less frequent, represented a significant portion of societal concerns, with aggravated assault leading the category at 26.0 per 100,000 residents. Over the next two decades, the index crime rate climbed steeply, peaking at 7,036.9 per 100,000 residents in 1981—a staggering 256% increase from 1960.

This surge was driven primarily by property crimes, which rose 244% during this period. Burglary rates quadrupled, increasing from 405.7 in 1960 to 1,967.0 per 100,000 residents in 1981, while larceny-theft rose by 210%, from 1,371.2 to 4,250.8. Motor vehicle theft (MVT) also rose sharply, increasing by 160%, reaching 340.4 per 100,000 residents in 1981. While property crimes made up the majority of offenses, violent crimes saw even sharper relative increases. Aggravated assault, for instance, grew by 869%, from 26.0 in 1960 to 251.9 in 1981, reflecting rising social tensions and shifts in criminal behaviour. Murder, though numerically small, doubled during this period, from 2.4 in 1960 to 4.4 per 100,000 residents in 1981.

The 1990s and early 2000s marked a significant shift, as crime rates began a sustained decline. Oregon’s index crime rate fell by nearly 44% between 1981 and 2006, reaching 3,952.4 per 100,000 residents. Property crimes led this decline, with burglary dropping by 59%, from 1,967.0 in 1981 to 806.6 in 1999, and larceny-theft decreasing by 45% over the same period. Violent crimes also showed notable reductions, with aggravated assault falling by 39% between 1981 and 2010, when it reached 153.5 per 100,000 residents. Legislative measures, such as the implementation of Sentencing Guidelines in 1989 and Measure 11 in 1994, likely played a role in these reductions by introducing more consistent sentencing practices and prioritizing violent crime prevention.

Recent years have painted a more mixed picture. While the long-term decline in property crimes has continued, certain violent crime categories have seen renewed increases. Between 2010 and 2022, aggravated assault rose by 45%, climbing from 153.5 to 222.7 per 100,000 residents. Motor vehicle theft experienced an even sharper resurgence, increasing by 126%, from 237.8 in 2010 to 536.3 in 2022, reflecting challenges in addressing specific offenses. Despite these increases, burglary rates have continued to decline, dropping from 645.2 in 2006 to 330.0 in 2023, a 49% decrease.

By 2023, Oregon’s index crime rate stood at 2,937.6 per 100,000 residents, significantly lower than its peak but reflecting recent increases in specific categories such as aggravated assault and motor vehicle theft. Violent crimes contributed 315.9 per 100,000 residents, while property crimes made up the remaining 2,621.7 per 100,000 residents.