INTRODUCTION

Following the defeat of Proposition 112 last year, two Boulder-based state lawmakers, House Speaker KC Becker and Senate Majority Leader Stephen Fenberg, have introduced a bill that would dramatically impact the way oil and natural gas development is regulated in Colorado: SB-181.ii SB-181 was introduced March 1 and as of this writing is barely a week old. In that time, SB-181 has already been pushed through three Senate committees and is widely expected to receive a Senate floor vote the week of March 11.

The rushed schedule for SB-181 has thus far prevented any substantive economic analysis from being conducted. The March 5 fiscal note prepared by Legislative Council staff finds that SB-181 will authorize restrictions up to and including “an outright prohibition of oil and gas development”iii at the state level and corresponding local measures that also “limit or prohibit oil and gas development.” But the fiscal note does not attempt to quantify the clear economic costs that would be incurred from the severe and sudden reductions in oil and natural gas permitting and production that are possible under SB-181.

Intended or unintended, the potential consequences of rushing SB-181 through the legislature without proper economic analysis are severe. Colorado is a major energy producing state, ranking fifth in oil and sixth in natural gas, and oil and gas constitute more than 85% of the energy produced in Colorado from all sources.iv According to a 2015 study from the Colorado Leeds School of Business the oil and gas industry contributed over $1 Billion in state and local tax revenue.v Therefore, sweeping new restrictions on one of the state’s largest economic sectors will be felt across the economy and across state and local budgets. This is common sense.

With the limited time available, this analysis attempts to quantify the range of economic consequences that may result from rushing SB-181 into law.

BACKGROUND ON THE DEBATE

Colorado has been a major energy producing state for decades. Recent population growth has resulted in new suburban development in areas that have long been producing oil and natural gas, and in particular, the DJ Basin in northern Colorado. Technological advances in the energy sector have also made these existing oil and gas fields much more efficient and productive, attracting significant new investment and infrastructure.

For more than 10 years, Colorado lawmakers and regulators have responded to these trends and the land-use challenges they present with successive waves of regulatory reform. This process began under Gov. Bill Ritter in 2007, with the passage of oil and gas legislation and a 19-month rule making process that completely overhauled the state’s regulatory framework and the structure of the Colorado Oil & Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC). At the conclusion of this process, state regulators declared “these rules will ensure the protection of the public health, safety and welfare, including the environment and wildlife resources” while also allowing for continued growth in Colorado’s energy sector.vi

The state’s regulatory framework has not been static since then – far from it. In the years since the 2007-2008 reforms, more than 15 major rule makings and regulatory actions have taken place across state government concerning the oil and natural gas sector. These reforms have included “expanded notice and outreach to local communities and heightened distances … between new drilling and dwellings,” new regulations to “further bridge the regulatory roles between state regulators and local jurisdictions and accelerate efforts by operators to work in closer fashion with local governments,” policies that encourage “agreements between local governments and operators” and the addition of regulatory staff “to work specifically with local governments,” according to the COGCC.vii

Last year, former Gov. Ritter said the state’s rules in 2008 were already “the toughest set of regulations for oil and gas development in the country” and they were strengthened further by his successor, Gov. John Hickenlooper. “Today, Colorado maintains its place at the top, with the most stringent set of state regulations governing oil and gas extraction,” Ritter said.viii

Ritter’s assessment was a direct response to Proposition 112, a 2018 ballot measure that would have imposed 2,500-foot drilling setbacks from occupied buildings and long list of so-called vulnerable areas on state and private land. The same ballot measure would also have given broad discretion to state and local officials to impose wider setbacks and designate additional vulnerable areas at will. Regulators determined, at a minimum, that these restrictions would prohibit new oil and gas development across 85% of state and private land in Colorado, with even greater impacts in the state’s top energy-producing counties.ix

The Denver Post editorial board, among many other observers, determined that Proposition 112 would “effectively ban oil and gas operations” across the state.x Colorado health officials also refuted a series of alarmist health claims made by the groups behind Proposition 112. The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) traced those non-scientific claims to oil and gas opposition groups in other states and additionally found those claims were not supported by more than 10,000 air samples and other research conducted here in Colorado.xi

This followed a 2017 report from CDPHE that examined air samples and a dozen different epidemiological studies and found “[n]o substantial or moderate evidence for any health effects.”xii The department continues to monitor the effectiveness of Colorado’s oil and gas regulations in real time and shares its findings with policymakers and the public.

Voters defeated Proposition 112 by a decisive margin – more than 10 percentage points – in November. But the same groups that supported Proposition 112 are now fully behind the effort to pass SB-181.

“We have to see that this bill passes cleanly,” said Joe Salazar, a former state legislator and the executive director of Colorado Rising, said before SB-181’s first hearing before the Senate Transportation and Energy Committee. xiii

KEY PROVISIONS OF SB-181

As introduced March 1, SB-181 is a 27-page bill that overhauls state regulations, the COGCC and hands new oil and natural gas regulatory powers to local governments. The bill’s authors have stated the intention of SB-181 is to provide additional health and safety protections and increase local involvement in oil and gas development siting decisions. If that is the case, the legislative language of SB-181 goes much further than what the authors have intended.

For this analysis, we focus on the following provisions of SB-181:

AUTHORITY FOR UNILATERAL MORATORIUM

Section 11 of the bill states the COGCC director may refuse to issue permits from the moment SB-181 becomes law until the COGCC has promulgated every rulemaking required by the legislature and those rules have entered effect. Exceptions to the permitting moratorium are possible, but only at the director’s sole discretion. There is no time limit on the rulemaking process or safeguards to prevent political directives or litigation from outside groups from indefinitely delaying the conclusion of the rulemaking process. As described earlier in this report, when the legislature conducted a major reform of oil and gas laws under Gov. Ritter in 2007, it took 19 months to complete the rulemaking process.

Given what is currently known about the scope of SB-181, this 19-month benchmark should be considered the bare minimum to complete the rule makings called for in the bill, and that process could last considerably longer.

In the days before the introduction of SB-181, the COGCC previewed how the agency’s new director may use this discretion. The agency announced a list of 19 new criteria that will trigger “additional director review.” Those criteria include a proposed well located in any municipality or within 2,500 feet – the same distance prescribed in Proposition 112 – of any municipal boundary, county line or platted subdivision. Permit applications could also be flagged by the director on behalf of the governor’s office for any reason, or flagged because of comments from an environmental group, among many other new screening criteria. There is also a catch-all category for permits the COGCC “believes may be otherwise hairy, sticky or likely to stand out.”xiv

REPEAL OF TECHNICAL FEASIBILITY AND COST-EFFECTIVENESS

Section 7 of SB-181 would remove technical feasibility and cost-effectiveness as factors that must be considered under the statute that governs COGCC permitting and regulatory decisions. In effect, this change would sideline economic considerations that are commonly used in other kinds of regulatory decision making – including those that prioritize health, safety and the environment. For example, the U.S. EPA has long considered “energy, environmental and economic impact” when determining the “best available control technology” for emissions from electric power plants.xv

SUBJECTIVE NEW RESTRICTIONS

Section 4 of SB-181 dramatically increases the authority that local governments would have over oil and natural gas permitting decisions. There is also broad discretion in how this authority could be exercised. Critics of the bill have noted that limitations, prohibitions or unlimited fees could be justified with references to “cultural resources” and “nuisance-type effects” which are highly subjective in nature.

REGULATORY UNCERTAINTY FROM CONFLICTING STANDARDS

SB-181 anticipates conflict between different agencies of state government and different local jurisdictions over whose rules should apply to oil and natural gas development. Section 15 of the bill states that whenever such a conflict exists, “the regulation or standard that is rationally designed to be more protective of public health, safety and welfare, the environment or wildlife resources” will prevail over all others.

Whenever such a conflict arises, permitting new oil and gas projects will become difficult to say the least, because of the confusion over which regulations and standards from competing jurisdictions will apply. This confusion is likely to last a significant period of time – preventing the approval of new permits – as the competing jurisdictions negotiate or litigate their differences in court.

ECONOMIC IMPACT SCENARIOS

Despite the stated intentions behind SB-181, the new authority granted under the legislative language leaves the future of the industry facing significant uncertainty. State agencies and local governments would have the authority to impose significant new restrictions on new oil and gas development. In fact, as Legislative Council staff have noted, these provisions do not limit the range of possible restrictions, up to and including “a prohibition of oil and gas development.”

While the exact number or type of permits that have been approved that violate the desired prioritization of health and safety have not been identified, the COGCC commissioner has made public the criteria for which he would select permits to be “flagged for further review.”

Initial list criteria of which an operator’s permits MAY be flagged released by COGCC

- Well (or production facility) located within 1500’ of residence or high occupancy building

a. Can be a singular residence

- Well located in municipality

- Well located in these counties: Boulder, Gunnison, Routt, Huerfano, Pitkin or Delta

- Well located within 2500’ of a different municipal boundary, platted subdivision, or county boundary

- Well is proposed to access minerals in a different governmental jurisdiction from the surface location

- A LUMA or UMA

- Well located in the school setback area

- Well in a flood plain

- Well located in the 317B buffer area or the Brighton water buffer area

- Well located in RSP or SWH for Greater sage Grouse or bald eagle

- Well to be operated by operator subject of increased bonding or protection

- Well proposed to be located in the exception zone location

- Any location added by Director (EDO, Gov’s office)

- Any location that OGLA has concerns with

- Right to construct is Surface Bond (operator Bond on)

- Application has received comments from local government, state or federal agency, including wells with CDPHE consult

- Application has received comments from environmental group or HOA or other group raising concerns

- Application requires director to grant a Rule 502.b variance

- Application the reviewer believes may be otherwise hairy, sticky, or likely to stand out

The combination of the possibility of a lengthy moratorium, the removal of technical and cost considerations, the subjective nature of the standards that must be met across each different local jurisdiction and the confusion and uncertainty generated by conflicting local standards are likely to result in significantly fewer wells being drilled. For example, in testimony to the Senate Finance Committee, an industry official said the passage of SB-181 would likely cut his company’s budget for capital expenditures – which are primarily directed towards drilling new wells – by 53%.

New drilling is essential to bringing new production online, because existing wells steadily produce less oil and natural gas over time. New drilling is also where most of the capital expenditure arises and is the most labor-intensive part of the production process.

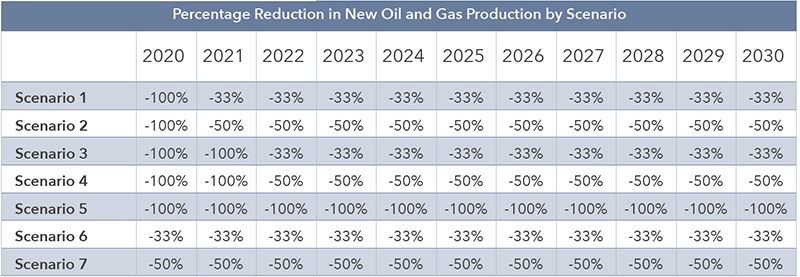

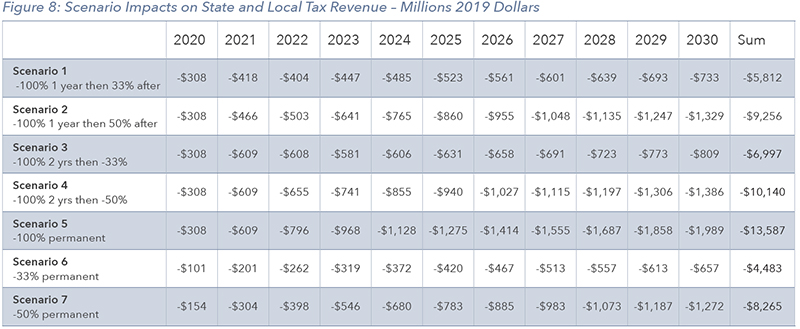

In this analysis, we examine 7 scenarios that explore a range of possible impacts on oil and gas production levels in Colorado following the passage of SB-181. These scenarios are not meant to predict the future, but rather offer some important insights into the connections between new oil and gas production, the economy and government revenue.

Much of the discussion during legislative testimony surrounded the worst-case scenario, resulting from total authority of the COGGC Director over the permitting process. To demonstrate the extent to which this would have near, and long-term impacts Scenarios 1-5 estimate the economic and fiscal consequences. What is currently unknown, is the length of time the current inventory of approved permits would be able to sustain production levels. We assume that if SB 181 is approved as is, prior to April, then if no new permits are approved, new production would not stop until 2020.

Scenario 1 – 100% decline in new production in 2020. Then from 2021 through 2030, new production would resume at 75% of the current baseline.

Scenario 2 – 100% decline in new production in 2020. Then from 2021 through 2030, new production would resume at 50% of the current baseline.

Scenario 3 – 100% decline in new production for both 2020 and 2021. Then from 2022 through 2030, new production would resume at 75% of the current baseline.

Scenario 4 – 100% decline in new production for both 2020 and 2021. Then from 2022 through 2030, new production would resume at 50% of the current baseline.

Scenario 5 – 100% decline in new production from 2020 through 2030.

Scenario 6 and 7, differ from 1-5 in that there is not a complete moratorium but rather significant slowdowns during the forecast period of 2020 through 2030.

Scenario 6 – 33% decline in new production from 2020 through 2030

Scenario 7 – 50% decline in new production from 202 through 2030

SCENARIO RESULTS

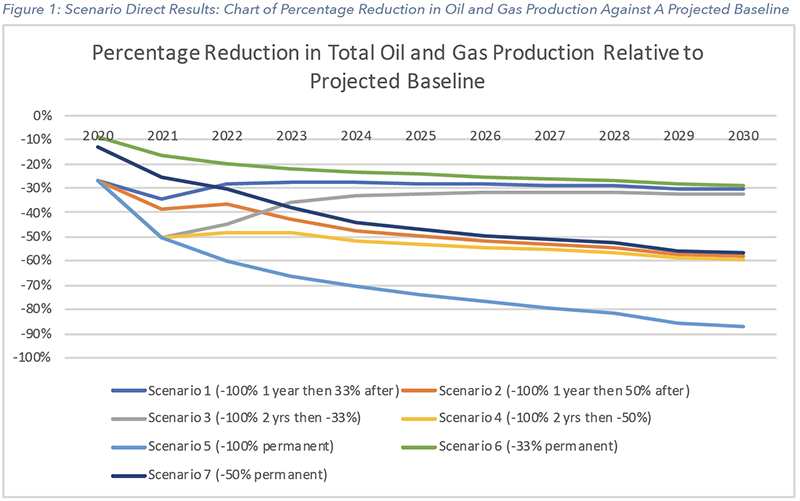

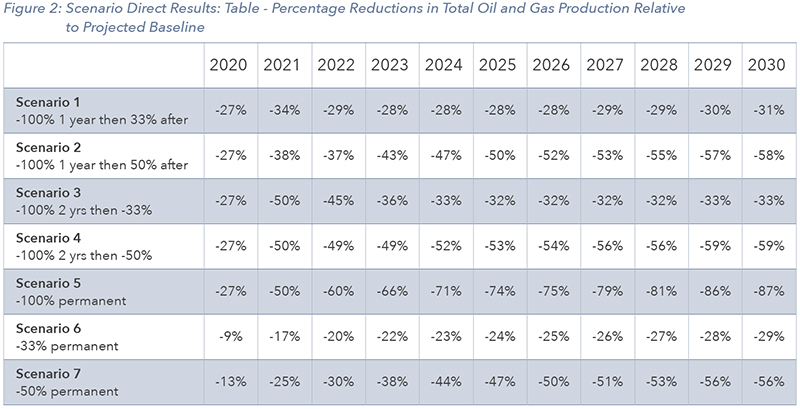

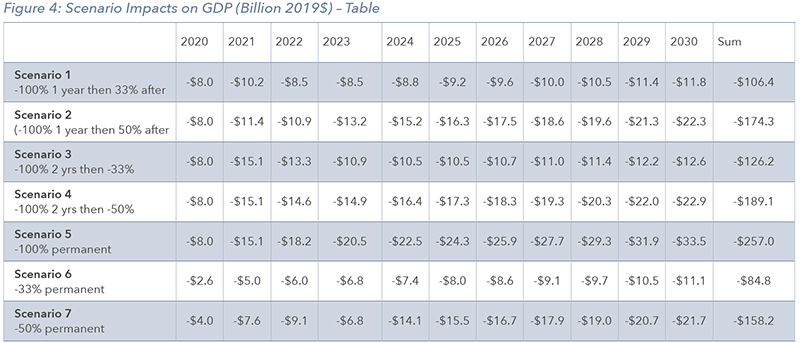

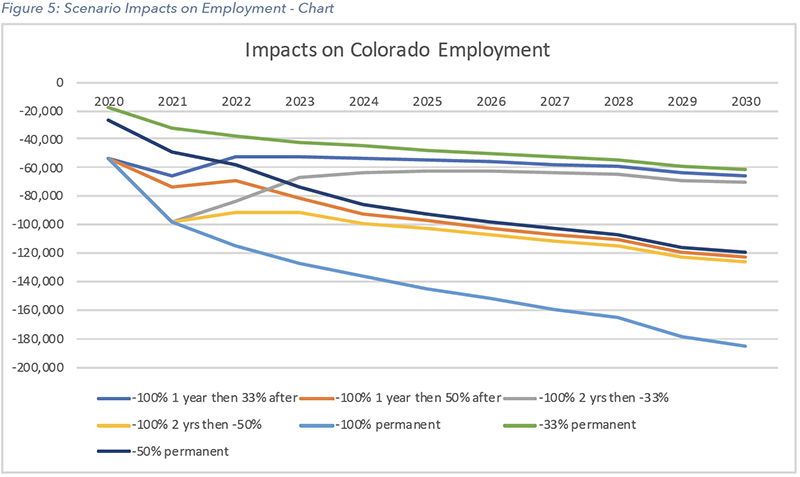

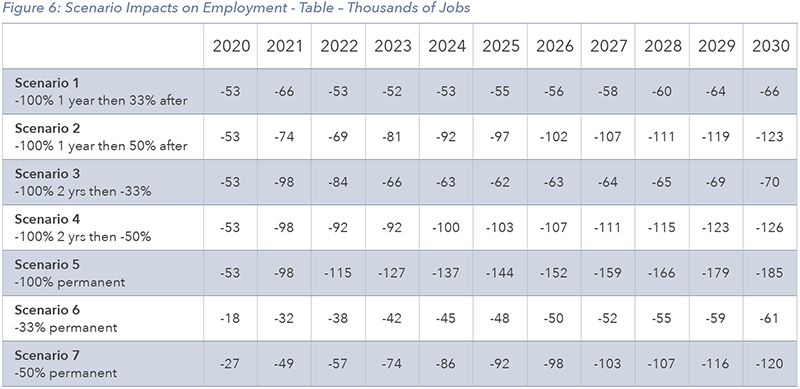

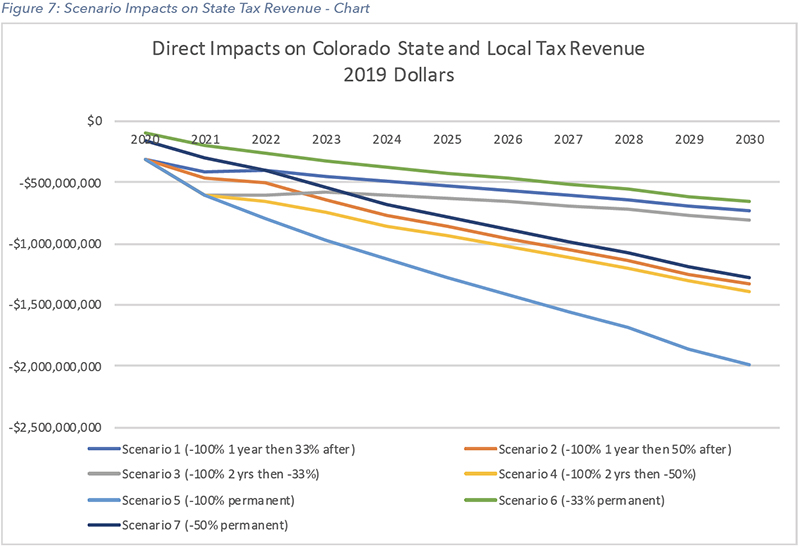

The following results show the direct and dynamic impacts to the Colorado economy of each scenario. The results show the impacts on statewide GDP, employment and tax revenue for each scenario outlined in the previous section.

The modeling performed to arrive at these results included multiple steps. It consists of establishing a baseline projection of oil and natural gas based in a projection of new wells and their annual production from 2020 through 2030 accounting for basin specific decline rates. Then for each scenario, the appropriate amount of new production is removed for each year. Future decline rates were then applied to the initial loss in new production and the associated future losses were also entered into the REMI Tax-PI model, as a percentage reduction in the NAICS oil and gas extraction industry.

The results should be interpreted as showing the impacts in each future year, relative to that future year’s baseline.

DIRECT IMPACTS

The values that are directly input into the simulation model represent the percentage loss in the oil and gas extraction industry. Given the way the scenarios were set up, it is easy to observe the three separate sets of impacts in the first year, 2022. All four of the scenarios that begin with a full year of no new production, have the same starting point for impacts in year one. From there, the impacts diverge as the future years play out differently.

Figures 1 and 2 show the estimated loss in the total production value of oil and natural gas across all of Colorado, resulting from each scenario. The scenarios are set up to estimate varying degrees of reduction in new production while allowing existing wells to continue to produce with forecasted decline rates. This dynamic is important to understand in interpreting the results. Through the forecast, existing wells are producing less and less, at the same time lower amounts of new production are coming on-line. Therefore, even with a consistent percentage of lost new production, the share of the total industry that is lost gets larger each year. As an example, losing 100% of production for 2020, would amount to a roughly 27% reduction in the entire industry. However, by losing new production for an entire second year would result in losing just over 50% of the entire industry.

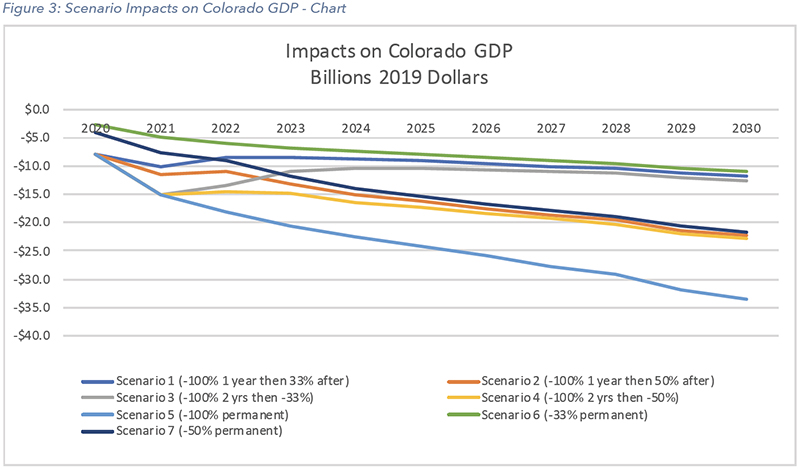

DYNAMIC IMPACTS

Figures 3 and 4 captures the statewide impacts on Gross Domestic Product (GDP) resulting from each scenario. GDP is the aggregation of value of final transactions, therefore it excludes double counting sales that serve as inputs to other products. The reported losses in GDP cover the impacts across all industries not just oil and gas extraction. These dynamic impacts aggregate the loss in value across the state as less production in oil and natural gas leads to less investment and impacts down the supply chain. It also captures the impacts resulting from less personal income, and the reduction in consumer spending on housing, health care, electronics, cars and other items.

Figure 5 and 6 provide an estimate of the impacts on employment across all sectors of the economy. The REMI model uses the employment data and definition used by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), which includes full-time, part-time and self-employed reported as one job.

A memo released January 2018 by the Colorado Legislative Council, estimated that the effective tax rate on the production value of oil and natural gas was 6.4%. Of the 9 states listed in the memo, 6.4% was higher than 3 states including Oklahoma but lower than 5 states including Wyoming, North Dakota and Texas. The effective tax rate captures taxes paid on production such as severance, along with property, income, and sales and use taxes. By applying the effective rate of 6.4% to the estimated value of lost production, figures 7 and 8 report the impacts for each scenario.

ADDITIONAL UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES OF SB 181

Economic and budgetary impacts of this magnitude would have far reaching consequences. The details of these consequences deserve more attention than the limited time available to analyze SB-181. That said, some general areas of concern can be flagged now so they are not completely overlooked in the SB-181 debate.

THE BACKFILLING OF REVENUE ACROSS PUBLIC EXPENDITURES

Public education funding, for example, is likely to suffer disproportionately from any reduction in oil and gas revenues triggered by SB-181. Just prior to the release of SB-181, a coalition of business, labor and civic groups in Colorado cautioned that the oil and gas sector is “one of the most significant sources of tax revenue for basic public services at the state and local level.” The business coalition said total oil and gas-related revenues currently exceed $1 billion per year, and highlighted K-12 and higher education as perhaps the biggest beneficiary.

xvi

THE DROP IN NON-RESIDENTIAL PROPERTY AND THE INTERACTIONS WITH GALLAGHER

During her testimony, the Weld County Assessor Brenda Dones, laid out a compelling argument for how large declines in oil and gas and their associated production and other non-residential properties could destabilize property taxes statewide. Due to the structure of the state’s Gallagher Amendment which governs the laws around property taxes, it effective sets a required split of the total amount of property taxes that can be collected from residential property and from non-residential property. That split is 45% residential and 55% non-residential. TABOR also restricts the increase of taxes without a vote of the people. Therefore, when there is a large decline in non-residential property from the loss in oil and gas production, the assessment rate for residential property also must fall to maintain the 45/55 split. That would result in significant declines in tax revenue for local entities such as schools, police and fire, if voters didn’t approve an offsetting mill levy increase.

IMPACT ON HOUSING DEVELOPMENT

With SB-181 receiving three committee votes less than a week after its introduction, other economic sectors besides the energy industry have had a limited opportunity to explore the second- and third-order effects of the bill’s state and local restrictions on oil and natural gas development. However, they have expressed major concerns about how these restrictions and regulatory uncertainty facing the state’s energy sector will impact investment decisions, employment levels and consumer demand across the state economy.

The Colorado Association of Home Builders (CAHB), for example, announced its opposition to SB-181 during the bill’s hearing in the Senate Finance Committee.xvii “Our position is based on the uncertainty caused by the bill – uncertainty for the fiscal impact to the state, but also uncertainty for our industry and for Colorado’s economy,” CAHB said in testimony to the committee.

Investments in home construction, especially in regions of the state where energy production occurs, depend on stable and certain rules. SB-181 sets up conflict between different levels of government and different local jurisdictions over which regulations apply, which “could hold up our surface use” until litigation over these conflicts is resolved. These delays will reduce the supply of newly built homes, “impacting our ability to address our housing affordability problem.” The home builders are also concerned about the impacts of declining energy production on the broader economy. In terms of jobs, this will be felt “in a negative way across the full spectrum, from accountants and software developers, to police, fire and teachers [and] construction workers.”

THREAT TO FISCAL SOLVENCY AND STATE’S CREDIT RATING

A sudden decline in public revenue could also undermine recent efforts to stabilize Colorado’s public pension system. Last year, in response to a $32 billion unfunded liability, lawmakers approved a $225 million annual payment from the state’s general fund to the Public Employees’ Retirement Association (PERA) and higher contribution rates from state agencies, school districts and other taxpayer-funded entities, among other changes.xviii

The $225 million annual payment and other changes to the state’s public pension system were designed to prevent a downgrade in Colorado’s credit rating, which would raise the borrowing costs for bond issues that finance road construction and other public infrastructure projects. But a sudden decline in oil and gas tax revenues may reduce the amount of money available in state, local and school district budgets to support the PERA stabilization effort, which began less than a year ago.

The potential impact on PERA’s long-term liabilities – viewed in isolation or in combination with broader budget challenges – would give credit rating agencies another reason to critically examine Colorado’s finances and potentially increase the state’s borrowing costs. In a major energy producing state like Colorado, energy policy is also fiscal policy, and therefore the impacts of a bill like SB-181 need to be viewed through a wider, whole-of-government lens.

CONCLUSION

The Colorado oil and gas industry is a major contributor to the state’s economy and faces perpetual negotiations over the regulatory framework that governs its operations. Over the past several years Colorado has continued to adopt new regulations to protect health, safety and the environment. In 2018 former Colorado Governor Bill Ritter stated, “Today, Colorado maintains its place at the top, with the most stringent set of state regulations governing oil and gas extraction.” Despite this, and the rejection of Proposition 112 in last year’s election, the Colorado legislature is swiftly moving a bill along that would overhaul how an industry that generates over $31 billion to the Colorado economy is allowed to operate. Senate Bill 181 creates enough uncertainty, and more than enough legal authority to force the questions about just how bad things might get. After reviewing the specifics of the bill, and modeling several economic scenarios, the answer is clear. Significant near-term and ongoing reduction in new oil and gas production would have consequences that ripple across the state, costing tens of thousands of jobs and billions in tax revenue.

ENDNOTES:

i https://www.denverpost.com/2018/10/15/ritter-ive-been-a-champion-of-oil-and-gasregulation-and-im-voting-no-on-prop-112/

ii https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/sb19-181

iii https://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2019A/bills/fn/2019a_sb181_00.pdf

iv https://www.eia.gov/state/?sid=CO#tabs-3

v https://www.coga.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/COGA-2014-OG-Economic-Impact-Study.pdf

vi http://cogcc.state.co.us/documents/reg/Rules/2008/COGCCFinalSPB_121708.pdf

vii https://firebasestorage.googleapis.com/v0/b/torid-heat-3070.appspot.com/o/Resources%2FCOGCCEffortsDecade.pdf?alt=media&token=3ca5c3bf-ca89-4128-b9e4-a0370c797c42

viii https://www.denverpost.com/2018/10/15/ritter-ive-been-a-champion-of-oil-and-gasregulation-and-im-voting-no-on-prop-112/

ix https://cogcc.state.co.us/documents/library/Technical/Miscellaneous/COGCC_2018_Init_97_GIS_Assessment_20180702.pdf

x https://www.denverpost.com/2018/10/10/proposition-112-is-ban-on-oil-and-gas/

xi https://denver.cbslocal.com/2018/10/23/reality-check-proposition-112/

xii CDPHE: Assessment of Potential Public Health Effects from Oil and Gas Operations in Colorado, Feb. 21, 2017

xiii https://www.energyindepth.org/hundreds-of-oil-gas-workers-pack-the-halls-of-coloradosstate-capitol-to-oppose-sb-181/

xiv Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission: Additional Director Review “Notice to Operators,” Feb. 19, 2019

xv https://www.epa.gov/nsr/prevention-significant-deterioration-basic-information

xvi https://www.cobrt.com/press-releases/oil-and-gas-debate-business-community-urgeslawmakers-to-respect-will-of-voters-find-common-ground/2/28/2019

xvii Colorado Association of Home Builders testimony to Senate Finance Committee, March 7, 2019

xviii https://www.copera.org/sites/default/files/documents/impactofchanges-18.pdf

Download a pdf of the study >>

Download a pdf of the Key Findings >>