Summary & Key Findings

Arizona’s fire districts are special taxing districts created by County Board of Supervisors that provide fire protections services within its boundaries.

The districts’ service area need not align with County, City or Town borders – areas which are served by generally funded local fire departments. Under current law, a fire district is funded by property taxes on district residents and may (if the district lacks sufficient property tax base) receive supplementary assistance from its creating county government. There are 144 fire districts in Arizona providing services to “roughly” 1.5 million Arizonans (approximately 21% of the state’s population)[i]. Each district is governed by and operates on behalf of Arizona residents within the district boundary (typically rural and unincorporated areas). The states more urban municipal areas typically have dedicated fire departments that are created and funded by cities.

Under current law, the vast majority of fire district revenue comes from locally assessed property taxes on property inside the district, with some secondary support from the county which hosts the district. Prop 310 proposes to supplement this local revenue with support from a statewide 0.1% general sales tax, raising $189.9 million in 2023[ii]. Statewide Transaction Privilege Taxes (sales tax) are paid by all Arizona residents and are intended to provide for the general operations and maintenance of state government. Over two-thirds of sales tax revenue is collected in Maricopa County[iii], the vast majority (though not all) of which is served by municipal fire departments and not fire districts.

According to a Common Sense Institute (CSI) analysis utilizing the Regional Economic Models, Inc. (REMI) dynamic economic modeling program, a twenty-year statewide 0.1-cent sales tax increase would:

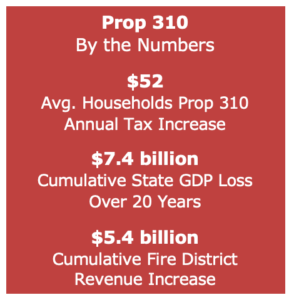

- Reduce statewide employment by about 2,500 jobs in 2023, increasing to approximately 3,800 fewer jobs by 2042.

- Reduce statewide Gross Domestic Product by a cumulative $7.4 billion.

- Reduce resident personal income by a cumulative $8.55 billion, or $690 million in 2042 alone.

- Increase the local price level by 0.04%, relative to baseline.

- Generate a cumulative $5.5 billion in additional fire district tax revenue, relative to baseline (approximately a 40% increase in statewide district revenue, depending on growth).

These impacts may be offset somewhat by increased fire district spending, though insufficient to offset the tax costs since the program (by design) will net transfer revenue from areas of high economic activity to areas of (relatively) lower activity. Because the tax increase is relatively small, CSI assumes there would be no secondary efficiency or competitive implications from the policy change beyond the directly measured taxpayer cost increases. To the extent these offsets occur, the true impacts of the tax could be smaller or larger than estimated here.

The operative question of policy interest is whether the $5.4 billion in additional fire district revenues over the next twenty years would provide sufficient statewide value to offset the $7.4 billion in economic costs. To the Institutes knowledge, no such analysis has occurred. Plan proponents have argued this proposal is necessary to shore up the smaller, more rural, and numerous fire districts with little property valuation and limited tax revenue (and indeed, a 2016 op-ed claims at that time 70% of the state’s fire districts collected just $50,000 or less in annual tax levy revenues[iv]). While the proposal institutes a 3% cap on initial round distributions, however, it generally favors districts with larger property valuations – meaning most of this money will likely end up going to the largest fire districts with the most local property development, relative to other fire districts.

Fire District (and Special Taxing District) Funding & Governance

There are at least 38 types of special taxing district authorized by state statute. In general, district oversight is provided by a local district-only board, elected by residents of the district, and there is limited statewide or external oversight. Often, special taxing district governance elections are uncompetitive (meaning candidates run unopposed), or insufficient candidates run to complete a board. While this creates significant governance and oversight risk, that is ameliorated somewhat by limited scope: these districts are generally only able to access within-district revenue sources subject to the approval of within-district voters.

The first Arizona fire districts were formed in 1918. Originally, fire districts were funded entirely by creating county governments, from county general funds – effectively making them the unincorporated equivalents to municipal fire departments. Over time, funding obligations have shifted to the district, as the districts gained increasing independence from the counties which formed them. In the mid-1980’s, however, the legislature created the fire distract assistance tax (FDAT) to try and correct for perceived inequities created by the entirely within-district revenue sources relative to other county and municipal services. The FDAT provides every Arizona fire district with supplementary access to a maximum of $400,000 in county funds, paid for by a countywide property tax.

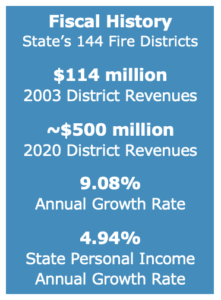

As of 2020[v], Arizona’s fire districts collected and spent nearly $500 million a year in property tax and other revenue, and a significant portion of those revenues go to covering unfunded public pension liabilities. For example, the twelve fire districts with the largest PSPRS unfunded liabilities accounted for more than half of all fire district spending ($273.9 million in budgeted revenues & expenditures in 2020) and had an average employer contribution rate of about 40%. Assuming that on average about one-third of expenditures by these districts goes toward wages and salaries, then approximately $36.15 million of all fire district spending in Arizona (7% of total expenditures) covers just the public pension costs at 12 of the states 144 districts. These same 12 districts could receive $104 million of the $189 million in additional expected fire district revenues, given the distribution formula considers only the relative property tax base of a district when sharing revenue (but subject to a 3% cap).

Between 2003 and 2020 fire district tax levy’s (and presumably spending) have increased from approximately $114 million[vi] to $500 million. It is difficult for CSI to better track annual, statewide revenues and expenditures over time by the state’s fire districts, as there does not appear to be any available source regularly tracking these figures.

Finding sufficient candidates to ensure competitive elections for the states hundreds of rural fire district boards has been challenging. In 2020, for example, none of the 19 fire districts in Maricopa County up for election appeared on the ballot; the few candidates who did file to run were unopposed and candidates were appointed directly by the county without public input. The lack of competitive elections and public interest creates significant opportunities for waste and abuse. Also in 2020, a former Mohave County fire district chief embezzled $40,000 from the district[vii]; in 2019 a Coolidge fire chief pled guilty to making $11,000 in unauthorized purchases on a district credit card[viii]; and in 2017 an administrator for the Show Low Fire District was found to have embezzled over $1.8 million in district funds[ix].

Under state law, special taxing districts – including fire districts – are required to produce annual financial reports; depending on district size these reports may be subject to prescribed regular and independent audit or review. However, the form and quality of the reporting can vary widely, and public accessibility is inconsistent. For most districts – where there are as few as one district statewide – this is a relatively minor problem. However, when there are hundreds of districts of massively disparate budgets, sizes, and scopes (as in fire districts), it makes drawing any kind of general conclusions time-consuming and costly (or practically impossible).

Proposition 310 Summary

Arizona Prop 310 would levy a new, statewide 0.1-cent sales tax for 20 years (beginning in 2023). Revenues collected would be deposited in the newly-created Fire District Safety Fund and distributed monthly to the state’s fire districts based on the district’s property valuation. The larger a fire district’s property value (relative to the total property value of all fire districts statewide), the more revenue that district would receive – except that no district could receive more than 3% of total revenues.

Under current law, the statewide sales tax rate is 5.6%, and the average Arizonan pays a combined tax rate of 8.4%[x] on most purchases. Prop 310 would raise these rates to 5.7% and 8.5%, respectively. CSI estimates that the proposal would increase the average Arizona household’s annual sales tax liabilities from approximately $4,351 to $4,403. Over two-thirds of this revenue would be collected from taxpayers in Maricopa County, which contains approximately 13% of the state’s fire districts.

The budget of the state’s largest fire district, Northwest Fire District (located in Pima County), is illustrative of the potential implications of this Act. The districts FY 2023 budget contemplates $72.8 million in revenue, of which $44.7 million (61.4%) would come from local property taxes. The District is likely to receive the statutory maximum of 3% of annual distributions from the Fire District Safety Fund (approximately $5.7 million). This would (relative to FY 2023 budgeted numbers) increase the districts total budget by about 8% and its ongoing budget by 10% (ongoing revenue is assumed to be the sum of property taxes, charges for services, premium charges, interest earnings, and other recurring transfers and revenues).

Proposition 310 requires fire districts to deposit Act monies in their general funds and permits them to use those monies for any purpose. There are no separate accounting or reporting requirements for district uses of these monies, or specific prescriptions on their use. While the Act includes a legislative intent statement asserting that fire districts are critically underfunded “leading to equipment shortages and extremely long response times”, no performance measures or benchmarks are established to track the new sales taxes impact (if any) of these monies on those issues, and districts would not be statutorily required to use any of the monies to resolve equipment shortages or lower response times.

Economic Implications & Proposed Improvements

To assess the economic impacts of the proposed 0.1-cent statewide sales tax, CSI utilized the REMI dynamic economic modeling program. Because the proposed tax increase is relatively small, we limited the analysis to just the direct impacts of the higher tax burden; we assess potential secondary incentive effects on economic investment in Arizona due to this tax to be minimal. Correspondingly, because the total revenues generated by the new tax are likewise de minimis (relative to total statewide public expenditures), and because the ballot proposition is vague on how the monies would be used, we likewise do not attempt to model potential economic benefits from the increased public spending. To the extent these assumptions are incorrect our analysis may under- or over-estimate the Act’s economic implications. For context, a 2017 federal study estimated nationwide economic costs of wildfire at approximately $209.7 billion[xi]. Assuming Arizona’s share of those costs is roughly $4.0 billion, then if the Act reduces annual economic damage due to wildfire on the order of 9.5% or more, it would be economically efficient.

For context on the relative scale of the Act, the baseline REMI simulation assumes Arizona’s Gross Domestic Product in 2042 will be $504 billion and cumulative output over the next twenty years will be approximately $8.7 trillion.

CSI assumes that, if enacted, Prop 310 would increase Transaction Privilege Tax liabilities by $189.9 million in 2023 and that this amount would increase by 3.5% every year through 2042 (when annual liabilities would reach $365 million). As a result:

- Arizona’s economy would be $450 million smaller in 2042 relative to a pre-tax baseline (or a cumulative $7.4 billion reduction over the next twenty years);

- Arizona would have 3,800 fewer jobs in 2042 and most of the foregone employment would be lost in Maricopa County;

- The states fire districts would receive a cumulative $5.5 billion in increased revenue, based on the JLBC fiscal analysis and 4% annual growth.

As we have said, the Act itself is vague with respect to how the monies would be used, and there is very little general and statewide data available about the fiscal performance of fire districts. However, CSI is aware of anecdotal data about district fiscal concerns, including:

- Waste and abuse of district revenues due to a combination of a lack of public interest and oversight and broad statutory powers.

- Large outstanding public pension liabilities in proportion to total budgets and payroll costs.

- Slow response times and uncompensated costs responding to fires, calls, and other emergencies originating with or attributable to non-district-residents.

Therefore, to improve economic outcomes if the Act is approved by voters, CSI would encourage districts and the public to consider:

- Ensuring new revenues generated under the Act are used to reduce existing liabilities and close existing resource gaps, rather than expand district payrolls and operations and ultimately exacerbate current fiscal woes.

- Plan in advance for how to manage the eventual expiration of the Act and its associated sales tax, including contingencies for both a true sunset or an extension. Too often the expiration of allegedly temporary revenue sources is treated as a fiscal cliff and used to effectively bully voters into approving extensions under threat of public safety job cuts and other unpalatable outcomes.

- Targeting revenues in a manner consistent with the legislative intent statement in the Act, particularly reducing response times, regardless of the broad spending authority granted districts by the statutory language.

- Separately accounting for the new statewide revenues in annual district financial statements, and disclosing both to local district residents and voters statewide how those monies were spent, again regardless of any broad authority or lack of reporting requirements included in the Act.

The ability of the State Legislature to intervene to improve the application or function of voter-approved ballot propositions is limited due to the 1998 Voter Protection Act. However, in this case, Prop 310’s included legislative intent clause may give the legislature potentially broader authority to consider intervention under the Voter Protection Act’s three-fourths “furthering the intent of” clause. We would encourage the legislature and its legal counsel to explore that authority if this proposal is enacted to ensure the efficient and prudent use of these new revenues. A combination of reporting requirements, including performance measure and benchmark recording, to a single statewide entity for collection and disclosure could improve public confidence in the administration and utilization of these new monies.

© 2022 Common Sense Institute

[i] “AFDA FAQ’s”. Arizona Fire District Association. Accessed on September 22, 2022.

[ii] Olofsson, Hans. “Prop 310 Fiscal Analysis”. Joint Legislative Budget Committee. July 22, 2022.

[iii] “FY 2021 Annual Report”. Arizona Department of Revenue. November 2021.

[iv] Morris, Gary. “Legislature needs to address crisis in fire districts”. Arizona Capitol Times. January 14, 2016.

[v] Stielow, Jennifer. “PSPRS COSTS PLAGUE CITY & FIRE DISTRICT BUDGETS”. Arizona Tax Research Association. October 2019.

[vi] McCarthy, Sean. “Pensions Anchor Fire District Budgets”. Arizona Tax Research Association. May 2014.

[vii] “Arizona fire chief pleads guilty to embezzling $40K”. The Daily Courier. January 6, 2020.

[viii] Khairalla, Rofida. “Coolidge fire chief pleads guilty to credit card fraud”. Coolidge Examiner. May 10, 2019.

[ix] Johnson, Michael. “County attorney: ‘She has nothing to show for $1.8 million’”. White Mountain Independent. June 2, 2017.

[x] “Taxes in Arizona”. Tax Foundation. Accessed on September 26, 2022.

[xi] Thomas, Douglas et. al. “The Costs and Losses of Wildfires”. National Institute of Standards and Technology. November 2, 2017.