Additional research by CSI has revealed changes in arrest and incarceration patterns consistent with policy changes to reduce the use of traditional law enforcement responses to incidents of crime. Between 1990 and 2017, the number of arrests for every reported crime in Arizona was steadily rising; this was coincident with steadily declining overall crime rates. At peak, there were nearly 0.5 arrests for every crime in Arizona, according to federal crime- and arrest-data (up from approximately 0.3 arrests per crime in 1992). In 2020, arrest rates per crime collapsed – to just 0.17 arrests per crime. Crime reporting rates also fell during this time, suggesting the policy change was broad; not only were police making fewer arrest, but victims were reporting fewer of the crimes committed against them (and prosecutors bringing fewer cases, etc.).

Four years on, it is now clear that this brief social experiment with tolerance for public nuisances has had dramatic consequences for quality-of-life not just for the homeless and the drug-addicted, but for property-owners and in particular commercial-property-owners. But these impacts have not been uniform; there are disparate regional impacts.

The Mechanics of Prop. 312

As referred to the ballot by the Legislature, Arizona Prop. 312 allows a property owner (without regard to the type of property) to apply for property tax refunds for the abatement of reasonable costs due to unmitigated public nuisances. For example, a property owner may be able to request a refund for cleanup costs associated with human waste, drug paraphernalia, and general refuse associated with public encampments, and open drug use.

The State Department of Revenue would be responsible for handling refund claims, and processing payments from the city- or county-share of state shared revenue they would otherwise receive. To approve a refund, the Department must first notify the impacted city or county; that local government would then have 30 days to accept or reject the request.

If rejected, the property owner could bring a civil claim in superior court for the denied fund, and the local government would be required to repay litigation costs if the property owner prevailed.

The proposed law specifically requires that the refund apply to documented and reasonable expenses. Examples in the law of unmitigated public nuisances that could give rise to a refund claim include patterns of tolerance of illegal camping, loitering, panhandling, and public use of drugs and alcohol by a city, town, or county government.

If enacted, the provisions of Prop 312 would apply to any property owner – including both residential and commercial properties. While in general the problem of both unsheltered homelessness and elevated density of property crimes seems to be concentrated around commercial and industrial areas, it is plausible that all kinds of property owners could have documented expenses eligible for property tax relief under this language (for example, home security equipment needed by a homeowner). According to court documents, the successful litigation against Phoenix over “the zone” involved both businesses and residents.[ix] For technical and data limitations reasons, though, this analysis is limited to the implications on commercia property valuation of unmitigated public nuisances (rather than the specific documented expenses that might occur and lead to refund claims, for any property type) – and if enacted the policy may induce increased enforcement and mitigation efforts by litigation-wary local jurisdictions, which could reduce both the valuation impacts and the need for private expenses.

Estimating the Impact of This Crisis on Property Values

In their ultimately successful lawsuit against the City of Phoenix over the semi-permanent public encampment now known as “The Zone”, plaintiffs (a group of residents and commercial property owners) alleged various public nuisances largely ignored by the City: a dramatic increase in violent crime; open drug use; property crimes; public waste and various biohazards; and a general increase in trash and refuse. The lawsuit provided various examples of documented expenses, including the need to install fencing and additional security, the repair of broken doors and windows, and the need for recurrent cleanup of human waste and other trash from both private property and even the adjoining public spaces (like sidewalks outside the businesses). The city in its response claimed, among other things, that these were isolated cases due to circumstances unique to the area (and the shelter presence there) and the issue was not unmitigated.[x]

To assess whether there is evidence of ongoing valuation impacts since 2019 due to potentially unmitigated public nuisances associated with chronic homelessness, public encampments, and open drug use, CSI took a two-pronged approach:

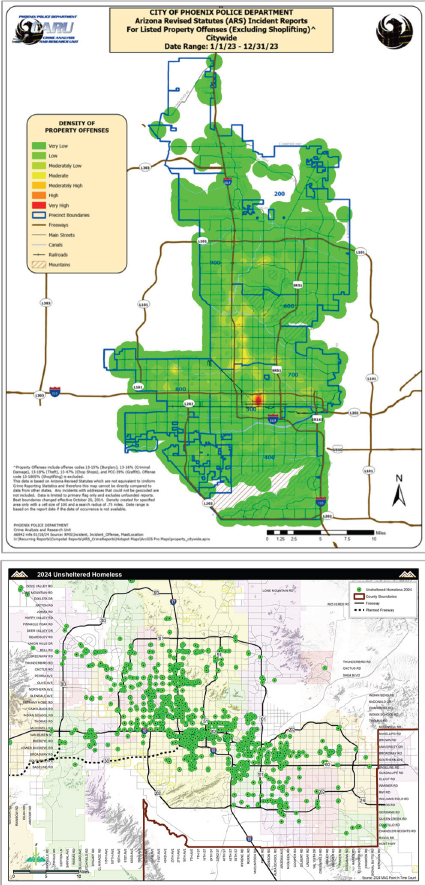

First, CSI identified areas within the City of Phoenix that had both

1. a high local homeless population (as measured by the Point-in-Time count and reported by the counts local administrator, the Maricopa Association of Governments),

2. and a relatively high incidence of property crime, as reported by the Phoenix Police Department in its regional map of local crime density.

Second, CSI utilized the Costar database of commercial real estate to identify properties and analytic data both inside and outside of these specific areas.[xi] CSI limited the analysis to commercial properties and the City of Phoenix due to data availability issues – specifically, only the City of Phoenix provides the detailed crime density mapping (and specifically to property crimes) needed in Figure 4.

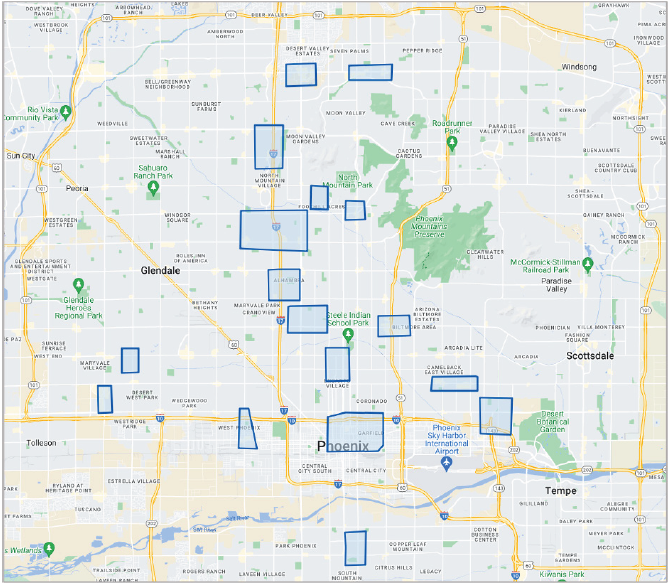

Immediately, apparent relationships manifest in the property crime and census of unsheltered homelessness data. Specifically, while there is a general dispersion of homelessness throughout the regional area, CSI was able to identify an apparent correlation between the density of the local county and reported property crime rates. One can easily identify the area of “the Zone” in both the property crime and unsheltered homeless maps; there are similar patterns apparent along the I-17 and light rail transit corridor, and in specific parts of North, West, and East Phoenix. Utilizing the polygonal dynamic mapping feature within the Costar database that enables the user to define their own area of interest, CSI translated these correlated regions into the Costar system (Figure 5); Costar was then able to provide detailed analytic data about commercial properties within these areas (as well as about property in the City of Phoenix generally, which provides our baseline for comparison).

For context, the Costar database identifies 26,092 commercial properties in the City of Phoenix; 3,950 of those properties fell within the geographic boundaries of the regions defined by CSI as having a relatively high incidence of both homelessness and property crime. Due to data limitations, not all identified properties are utilized by Costar in its analytic data – a net of approximately 20,278 properties were utilized by Costar to evaluate our City of Phoenix baseline, and 3,254 were utilized to provide analytics about out defined area in Figure 5.

According to Costar, between 2019 and 2023 the size of the Phoenix commercial real estate market grew by 5.2%. The estimated market asking rent[2] for a commercial space increased 30.2% over the same period (from an estimated $14.13/sqft in 2019 to $18.41/sqft in 2023). Vacancy rates for studied spaces declined 13.6%, reflecting the tightening of Phoenix’s commercial real estate market over this period (coincident with general rapid growth in the region identified by CSI in its other work, including the rapid appreciation of the areas housing market).

While Costar does not provide general estimates of property values, it does provide records of actual sales data – including average sales prices. Between 2019 and 2023, the average sales price for properties sold in Phoenix increased 25.5% (from $152.75/sqft to $191.75/sqft).

On the other hand, commercial property within the areas defined in Figure 5 (at high risk of an unmitigated public nuisance) saw their Costar-estimated market rents appreciate by only 15.7% over the 2019-2023 period (or about half the rate for Phoenix as a whole). General inflation over the same period was approximately 20%, meaning market rents in parts of the City with a combination of both high unsheltered homelessness and a high incidence of recent property crime fell in real terms over the past four years.

In terms of square-footage, the commercial real estate market in these areas was effectively flat (versus +5% growth in the city overall); there was 45.9 million sqft of commercial real estate in these areas in both 2019 and 2023. While overall vacancy rates were in decline over this period, vacancy rates within the areas identified by CSI increased over the past five years (from 12.57% in 2019 to over 14% today).

Noting again that this data is limited only to those properties that sold during the calendar year, the sale price for properties potentially impacted by unabated public nuisances in Phoenix increased by just 19.4% (again versus 25.5% in the city as a whole). Given the large potential for selection bias in terms of what properties are most likely to be offered for sale and then successfully sold, this likely understates the actual valuation implications.

Given the availability of Costar-estimated market rents, one tool available to CSI for estimating the potential overall valuation impacts of unmitigated public nuisances of the sort contemplated by Prop. 312 is the Gross Rent Multiplier (GRM) – or more simply, a value-to-rent ratio, which attempts to estimate a property value via a fixed ratio of its rental rate. A reasonable assumption is that GRM for most commercial properties lies in a range of 8-12.[xii] Utilizing the relatively large volume of annual sales data and estimated market rents available in the Costar database for the entire Phoenix area, CSI estimated a GRM of 10.8 for the Phoenix market in 2019 and 10.4 for the market in 2023.

Based on this ratio, the implied valuation of all commercial real estate in the Costar Phoenix database in 2023 was $67.9 billion (+32.1% since 2019). Correspondingly, the implied valuation in areas that may have had unmitigated issues of loitering, illegal camping, and property crime since 2019 was $11.7 billion (+11.6% since 2019).

This suggests a potential loss in commercial property value due to problems associated with unmitigated public nuisances since 2019 of up to $2.1 billion, if those properties would have otherwise appreciated at a comparable rate to Phoenix generally. Although the areas identified by CSI encompass broad parts of the city and are relatively diverse across various measures, it is possible that these properties and regions are generally less desirable and those market issues are not entirely attributable to recently rising crime, homelessness, and drug use.

Additionally, it is important to note that this does not imply potential claims under Prop. 312 in the order of several billion dollars. Only reasonable and documented expenses in response to specific case of unmitigated nuisances would qualify under the proposed language, and it is unlikely that a general loss of value (or, even more abstractly, loss of potential appreciation in value) would meet this standard.

However, this analysis provides some objective substantiation for the claim that documented increases in crime rates, chronic homelessness, drug use, and other public nuisances since the pandemic may be generating real and ongoing economic impacts for property owners in Phoenix (and potentially beyond). This data may also be of use to the public in evaluating the relative merits of Prop. 312 against the suggestion that there were specific and isolated issues related to “the Zone” in Phoenix that do not necessarily require a statewide and ongoing solution.[x iii]

iii]

A Study of Specific Properties

Costar does not provide information about criminal or nuisance activity within its data. However, CSI did identify a small and random subset of specific properties in or near areas it defined in Costar, and utilized an external community crime map[xiv] to measure relative crime rates within half a mile of those properties. It then compared those crime rates to implied crime rates one might expect in any given 0.5-square-mile area of Phoenix, based on estimates constructed using crimegrade.org data.[xv]

CSI examined three service stations, one day care center, and one sandwich shop. The names and addresses of these locations are provided in the Appendix accompanying this report. Across those five properties and over the most recent 1-year period reported by LexisNexis, there were an average of 108 reported drug crimes within a half mile, 96 reported burglaries, 26 reported robberies, and ~1.5 reported arsons.

CSI estimates that a representative average half mile area in Phoenix should expect to experience 20 reported drug crimes, 8 reported burglaries, 1 reported robbery, and approximately 0 reported arsons. Meaning crime rates at selected properties were between 3 and 5 times higher than the “expected” crime rates in Phoenix overall.

The Bottom Line

Prop. 312 proposes to allow property owners a refund for documented reasonable expenses incurred mitigating an unaddressed public nuisance. Data suggests unsheltered homelessness, crime, and drug use have all increased in Arizona since 2019. This report extends these results to property values: areas with the potential to have been most impacted by increasing public nuisances since 2019 have seen less value increase than other commercial properties.

Prop. 312 wouldn’t compensate property owners for any perceived valuations loss, though – it requires documented mitigation expenses. These are harder to estimate. In practice, though, the real impact of tools like this on the books tends to be preventive: to avoid costly litigation and refunds, local governments may ultimately be more proactive about mitigating these nuisances if this proposal is enacted than they are today.

Appendix

CSI identified and estimated relative local crime rates for the following five locations in Phoenix:

Sandwich shop at 1301 W Jefferson St.

Day care center at 725 E Brill St.

Service station at 8004 N 27th Ave.

Service station at 1834 W Grant St.

Service station at 2840 W Cactus Rd).

Each location was chosen randomly based on the availability of Costar data and presence within areas identified by CSI for study in this report. All claims about these locations rely on publicly available data sources and are subject to all inherent risks and uncertainties that carries.

[1] Specifically, CSI used the Costar commercial real estate database and Lexis Nexis Community Crime Maps. Much of the location-specific data was only available for commercial properties.

[2] Costar uses its analytic data to estimate market rental rates for the universe of commercial properties within its software. This figure is an estimate but is not limited to only the subset of those properties with available leasing data.