Introduction

Denver is mired in a deeply unaffordable housing market, with an estimated housing unit deficit ranging up to 18,910 units. Over the past decade, the number of hours required to work at the average hourly wage to afford the mortgage on a newly purchased average-priced home in Denver has skyrocketed by 176%, increasing from 38 to 105 hours.[i] Although wages in Denver have risen by 44% during this period, they have significantly lagged behind the rise in housing costs.

Housing affordability is a critical issue influencing children's future earning potential, consumer sentiment, migration patterns, economic development trends, and homelessness.[ii] Denverites experience these pressures acutely, as the negative externalities of an unaffordable housing market reverberate throughout the community, straining families and local resources. In response to this crisis, leaders, policymakers, and analysts have proposed and implemented a variety of policy interventions aimed at increasing housing affordability in Denver.

This report examines the impact of Denver’s 2022 inclusionary housing ordinance, “Expanding Housing Affordability.”[iii] This policy requires a portion of new housing developments include a share of below market affordable units or pay a fee. It also increased the city’s linkage fee, applied to all new housing developments.

This report seeks to identify the strengths and weaknesses of Denver's ordinance and offer insights into potential strategies for effectively addressing the housing affordability crisis. To provide a robust analysis, Denver's outcomes are compared to permit data from comparable cities during the same period. Additionally, this report compares the project budgets of a multifamily development in Denver versus Aurora, highlighting how Denver’s ordinance contributes to higher per-unit costs and lower profitability.

Key Findings

- -2,890 to -3,180 housing units – Denver is permitting approximately 241 to 265 fewer housing units a month or 2,890 to 3,180 fewer units per year than it would be without its inclusionary housing ordinance.

- -31% vs +18% - While Denver’s housing permitting has declined 31% since the implementation of its Expanding Housing Affordability (EHA) Ordinance relative to the prior 6 years, permitting in Aurora has increased 18%. From September of 2023 through May 2024 Aurora consistently issued more housing permits than Denver despite having a population roughly half the size.

- Denver’s inclusionary housing ordinance significantly changes the financial viability of new development projects. – A representative 250-unit multifamily property looking to develop in Denver or Aurora, would need to increase rents by $80 a month or $964 a year per unit in Denver, to achieve the same return. For projects that do move forward, this acts as a hidden tax on renters. The return on equity was reduced from 2.17 to 1.83, a 16% decrease, between Aurora and Denver over a 10-year window.

- Additional Constraints on Housing Development - Denver’s housing crisis is exacerbated by the city’s zoning policies, with 77% of residential land dedicated to single-family homes. This restriction limits the development of affordable, denser housing types. The city’s lengthy permit approval process — averaging 206 days for major multifamily projects — causes further delays and increases costs, stalling much-needed housing development.

- Need for Zoning Reform and Fast-Track Permitting - To address its housing shortage, Denver should revisit its current policy approach emphasizing tax increases, subsidies and inclusionary housing requirements. Instead, reforming zoning regulations to increase capacity for more affordable housing and implementing fast-track permitting processes should be prioritized. Other cities that have successfully adopted these measures significantly sped up housing development and reducing costs.

Fundamental Challenges: Addressing Inefficiencies, Expanding Zoning Capacity, and Streamlining Permit Processes

While it is fashionable to blame housing developers for the unaffordable, high cost of housing, specifically market rate developers, experts agree that the key factor driving high housing costs is the acute housing unit deficit.[iv] Denver's housing shortfall has consistently failed to meet the demands of residents, many of whom moved to the city for its strong economy and desirable lifestyle. Though it has changed in recent years, robust net migration has outpaced the number of available housing units, causing housing prices and average rents to skyrocket over the last decade.

This shortfall is the culmination of many factors. One of the most important, yet least discussed, is the inefficiency of the home-building sector.[v] Homebuilding labor hour efficiency gains lag significantly behind other economic sectors. Today's homes, which are largely similar to those built decades ago, cost more per unit and take longer to develop than ever before. This inefficiency stems from the highly fragmented regulatory framework. Varying building and zoning codes across local jurisdictions hinder standardization of products, processes, and materials. This creates a bespoke, project-based building approach that limits standardization and repetition, resulting in a low-productivity growth industry.

Compounding the problem, cities across America, including Denver, dedicate the majority of their built environment to the most expensive housing product type—single-family homes, which house the fewest individuals per acre. As of 2023, Denver dedicates 77% of its residential zoned capacity to single-family homes.[vi]

Consequently, Denver faces significant housing affordability challenges, which are impacting the city's ability to attract new residents and businesses alike. Some cities including Minneapolis, Austin, Spokane, and Portland, Maine and Portland, Oregon have activated additional zoned capacity, by-right, across all single-family only zoned land. This has allowed for more affordable housing types like duplexes, triplexes, and quads, often referred to as the “missing middle” or “light touch density.” Denver has more recently taken a different tact, focusing primarily on inclusionary zoning, property and sales tax measures.[vii][viii] Since 2002, these policies aim to fund affordable housing in mixed-income communities. In 2015, Denver voters passed a residential and commercial property tax and linkage fee on new market-rate developments that do not designate a percentage of units as affordable. It is expected to raise $150M over a decade for affordable housing development.[ix] A 2020 voter approved sales tax of .25%, raises $40M to create a Homelessness Resolution Fund. Most recently, in July 2022, Denver implemented Expanding Housing Affordability (ESA), which went into effect for new developments in May 2023, with extensions granted until 4/18/2025.[x]

The headwinds to housing affordability extend beyond a fragmented regulatory marketplace and severe limitations on the percentage of zoned capacity for denser, market-based, attainably priced housing types. Lengthy permit-approval times for housing development applications significantly increase development costs.[xi] These delays can be catastrophic, raising the cost per unit by 1% per month based on a recent study from Washington State, and can eliminate the viability of projects due to the time value of money.[xii]

Denver has struggled in this regard as permitting times as of August 13th, 2024 are averaging 206 days to review major commercial projects, which includes multifamily housing.[xiii] While a 6 months review time is an improvement over earlier in 2024, where review periods routinely eclipsed 300 days or ten months, multifamily housing permits are down 55% in 2024 from prior 7-year average and 40% from 2023, which may be influencing recent permit review efficiency gains.

Over a 10-month period, the entire financial landscape can and has changed. The delays in project permitting and the rapid change in the average 30-year fixed rate mortgage and the federal funds effective rate have caused greater market uncertainty. Home buyers can no longer qualify for mortgages following interest rate hikes and projects that were viable at the point of application, are no longer.

Figure 2

Denver should be commended for making progress to reduce permit review timelines and streamline some land use regulations through a $4.5M HUD Pro Housing Grant and the creation of the Affordable Housing Review Team, dedicated to expediting the permitting of 100% affordable housing developments.[xiv] However, despite these efforts to shorten permit approval times, particularly for single-family and duplexes, Denver's multifamily permitting process still lags behind innovative approaches seen in cities like San Diego and Los Angeles.[xv] Both Mayor Todd Gloria of San Diego and Mayor Karen Bass of Los Angeles have issued executive orders for fast-track approvals with timelines demonstrating a sense of urgency not yet seen in Denver. Their results raise eyebrows and should raise the interest of city leadership.

As of January 2023, Mayor Gloria in San Diego directed city staff to approve development applications for 100% affordable housing projects within 30 days and issue certificates of occupancy within 5 days, via their process called Affordable Housing Permit Program Now.[xvi][xvii] This process details their program’s “Readiness Criteria” which specifies exactly what constitutes a complete development application submittal.[xviii] The program is proving effective. Since the launch of the fast-track program, projects have been fully reviewed in an average of nine days.[xix] By March 2024, 21 projects totaling 2,356 units have been fast-tracked, with 13 of these projects already under construction. Importantly, total permitting has remained elevated and even increased in recent months.[xx]

In Los Angeles, Mayor Bass issued a directive in December 2022 for city staff to approve development applications for 100% affordable projects within 60 days and to provide a certificate of occupancy in 5 days or less.[xxi] The city reported a large influx of interest receiving applications for over 18,000 proposed units through mid-2024. However, due to intense pressure from neighborhood preservation groups, the Mayor exempted several historic-designated communities from the order, which greatly reduced the number of locations eligible for fast-track approval, throwing cold water on permit applications. What started as more transformative reform has become another example of the ever-present, turbulent nature of land-use politics. Yet while Mayor Bass has significantly narrowed the scope of eligibility, San Diego continues to advance its program.

The substantial number of units under development in San Diego and permitted in Los Angeles underscores the powerful financial incentives facilitated by “by-right” permitting policies. These policies create a regulatory environment that significantly enhances project viability, enabling housing developments to succeed where they might otherwise falter without the greater clarity and predictability into the permitting process. The strong returns observed suggest that reducing permitting review times may be the most effective tool—aside from increasing zoned capacity—available to local governments. This strategy lies entirely within a local government’s control and is essential for fostering a regulatory environment that gives home builders the best chance to develop affordable, attainable and market rate housing within prevailing market conditions.

Impact of Inclusionary Housing Ordinance on Denver's Housing Permits: A Comparative Analysis

Denver's Expanding Housing Affordability (EHA) plan aims to create mixed-income communities by linking new market-rate housing to affordable units. It requires that new housing developments with 10 or more units include a share of units that are to be sold or rented to lower income households. This type of policy is often referred to as an inclusionary housing ordinance (IHO), or an inclusionary zoning policy, and was implemented in Denver in July 2022. To mitigate the impact on developers, the plan includes zoning and financial incentives designed to increase housing supply and reduce costs. Additionally, linkage fees - which just increased on 7/1/2024 - are utilized to fund new affordable housing, with exemptions for projects that include affordable units.[xxii]

Developers of 10 or more for-sale or for-rent housing units must comply with affordability requirements through two main options or alternative compliance measures. Depending on certain criteria they must allocate 8% to 15% of units as affordable per the inclusionary housing ordinance.

Incentives offered include parking reductions, permit fee reductions, and additional bonuses for exceeding the requirements, such as height increases and parking exemptions near transit. Alternative compliance options provide some flexibility, including fees in-lieu of affordable units, land dedication, or developing fewer units with deeper affordability. Figure 3 shows the different compliance options along with available incentives.

Figure 3

|

|

|

High Markets

|

Typical Markets

|

|

Options 1

|

Rental housing

|

10% of total units at 60% AMI*

|

8% of total units at 60% AMI*

|

|

Ownership Housing

|

10% of total units at 80% AMI

|

8% of total units at 80% AMI

|

|

Option 2

|

Rental housing

|

15% of total units serving an effective average of 90% AMI

|

12% of total units serving an effective average of 90% AMI

|

|

Ownership Housing

|

15% of total units serving an effective average of 70% AMI

|

12% of total units serving an effective average of 70% AMI

|

*AMI= Area Median Income. Source: https://denvergov.org/Government/Agencies-Departments-Offices/Agencies-Departments-Offices-Directory/Community-Planning-and-Development/Denver-Zoning-Code/Text-Amendments/Affordable-Housing-Project

The measure also increased associated linkage fees which impact single family housing.

Figure 4 – City of Denver Linkage Fee Chart

Source: Image from City of Denver[xxiii]

The Denver Mayor’s Office believes these measures, combined with the provided incentives and alternative compliance options, will foster, rather than deter new housing development by making it both feasible and attractive for developers to build affordable housing.

However, since Denver's EHA went into effect, the city has seen a 31% drop in the number of permitted units compared to the average from 2017 to June 2022. While construction slowed nationally following the rise in interest rates, an examination of permitting performance in Denver relative to Aurora and other peer cities, Salt Lake City and Boise, provides strong evidence of the EHA program’s adverse impact on new housing construction.

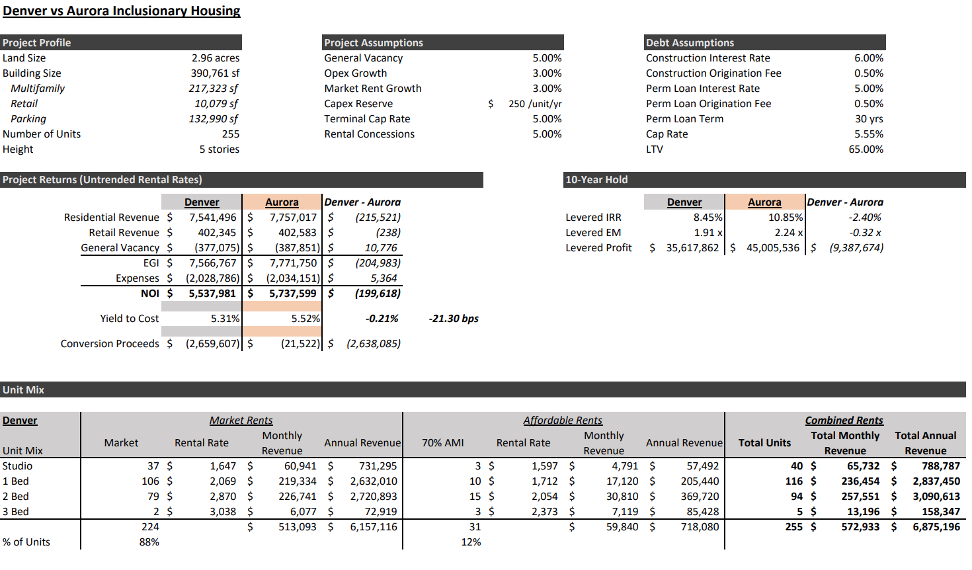

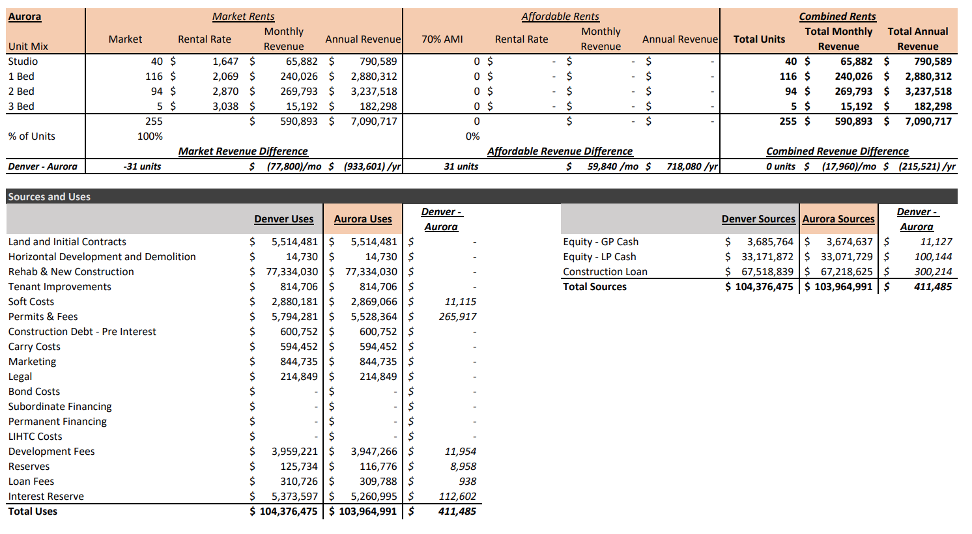

First, to understand the impact of the EHA program broadly, it is helpful to understand how it impacts a single project. Comparing the financials of an example 225-unit multifamily project currently in pre-development, in both Denver and Aurora, demonstrates the impacts of the EHA. The projects are identical in terms of construction pricing and market-rate rents, with data current as of August 2024. Since both cities fall within the same HUD primary market area designation, the comparison provides a clear view of how the EHA impacts project outcomes across similar markets.

Figure 5

|

Land Size

|

2.96 acres

|

|

Building Size

|

390,761 sf

|

|

Multifamily

|

217,323 sf

|

|

Retail

|

10,079 sf

|

|

Parking

|

132,990 sf

|

|

Number of Units

|

255

|

Figure 6

|

|

Denver

|

Aurora

|

Difference

|

|

Project Returns

|

Residential Revenue

|

$7,541,496

|

$7,757,017

|

-$215,521

|

|

Retail Revenue

|

$402,345

|

$402,583

|

-$238

|

|

General Vacancy

|

-$377,075

|

-$387,851

|

$10,776

|

|

Effective Gross Income

|

$7,566,767

|

$7,771,750

|

-$204,983

|

|

Expenses

|

-$2,028,786

|

-$2,034,151

|

$5,365

|

|

Net Operating Income

|

$5,537,981

|

$5,737,599

|

-$199,618

|

|

Yield to Cost

|

5.31%

|

5.52%

|

-21.30 bps

|

The comparison between the Denver and Aurora projects reveals a meaningful financial disparity. The EHA ordinance contributes to Denver's net operating income (NOI) being $199,618 lower than Aurora's. This is fundamentally driven by lower rents of designated affordable units, of $215,000. Over a decade, the expected return on the capital investment, as measured by the levered equity multiple (figure 10) is just 1.91 in Denver compared to 2.24 in Aurora. This is also reflected in the project’s internal rate of return (IRR) of 8.45% in Denver, 22% lower than Aurora's 10.85%.

For the Denver project to be as attractive as the Aurora project, rents per unit would need to increase by $80 a month or by $964 a year. This reflects the inherent tradeoff new development faces. Increase rents or find an alternative location.

For the purposes of analysis, project costs were assumed to be very similar between cities. The biggest difference being in the category of permits and fees, with Denver being $265,917 higher. The costs in this analysis are conservative as they do not include compliance-related costs that developers incur by having to maintain the income standards of their tenants as specified by the law. They also do not include any other cost factors unique to each city such as Denver’s green roof’s initiative, or increased energy efficiency standards.

See the Appendix for further project details.

These additional costs influence developers' decision-making, especially in this period of challenging capital markets. Every dollar counts and can be the difference between attracting housing development or discouraging it. As developers weigh these financial considerations, the higher costs associated with Denver's policies may deter investment, potentially pushing development to neighboring areas like Aurora where the regulatory environment is more favorable, allowing deals to pencil while they may not in Denver.

The financial impacts of this sample project are playing out across every new potential housing development in Denver. While Denver has seen a 31% decline in housing permitting, Aurora experienced an 18% increase.

While Denver has a population 1.8 times higher, or nearly double that of Aurora, housing permitting was higher in Aurora from last fall through May of this year. In the months prior to the start of the IHO, permitting in Denver was twice as high as Aurora.

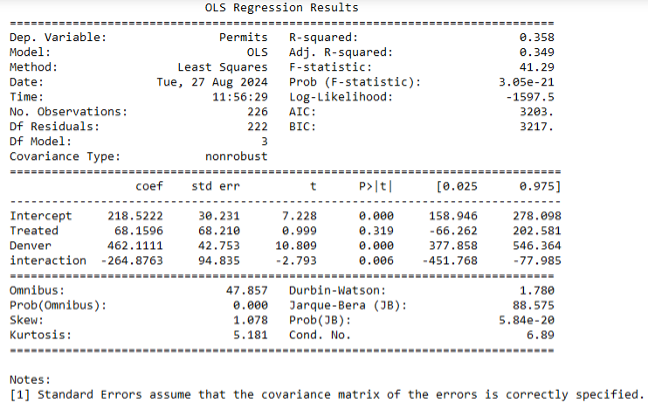

Figure 7

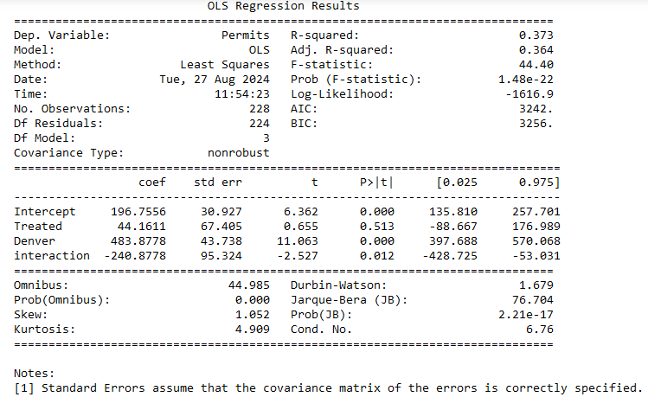

A detailed statistical analysis shows that Denver is permitting between 241 and 265 fewer homes each month due to the IHO. A formal difference-in-difference regression analysis comparing the number of units receiving a building permit each month in Denver and Aurora before and after the institution of Denver’s IHO in July 2022 shows that Denver is permitting as many as 265 fewer units each month due to the IHO. The analyses are statistically significant at the 5% level. This strongly suggests that the EHA is restricting supply which drives up housing costs for everyone, indicating that the plan is not unfolding as Denver had envisioned.

Compared to other metropolitan areas in the Mountain West region, Denver saw a significant rise in permitting in the second half of 2020. However, starting in July 2022, when the EHA took effect, there has been a steep decline in permitting. Permitting counts in Salt Lake City and Boise also dropped but not of the same magnitude.

Conducting the same difference-in-difference analysis comparing Denver to Boise and Salt Lake City, the results are similar. By this comparison, Denver is producing 241 fewer units per month, strongly corroborating the comparative analysis with Aurora. Importantly, permitting is down in each of these cities from their June 2022 levels. This is largely due to national factors described earlier. The difference-in-difference approach accounts for these wider economic headwinds and teases out the independent impact of the EHA.

Based on this analysis, and preliminary permitting data through June, if Denver did not implement the Expanding Housing Affordability ordinance, the city would have issued 33% to 35% more monthly permits.

Prior CSI analysis showed Denver needs to be issuing permits for between 5,322 and 8,927 housing units annually to close its supply gap by 2028. For the first 6 months of the year, Denver is averaging 383 units permitted. If this trend holds, the city will permit just 4,600 units, falling outside of the range needed. If not for the EHA policy, Denver permitting would be in the range needed.

Figure 8

|

Low

|

5,322 units

|

|

High

|

8,927 units

|

|

Annual Reduction in Permits Following IHO

|

This stark difference highlights how the EHA ordinance may be materially impacting Denver's housing supply, potentially exacerbating the ongoing affordability crisis. In contrast, three comparable cities without inclusionary housing laws, yet facing the same capital market challenges—such as high interest rates and scarce labor supply—are not experiencing the same constraints.

Figure 9

Addressing the Paradox: Revising Inclusionary Housing Policies and Implementing Fast-Track Permitting to Enhance Housing Development and Maximize Zoning Reforms in Denver

Across America, over 886 jurisdictions in 25 states have implemented some form of Inclusionary Housing Ordinances (IHOs).[xxiv] In contrast, only a few jurisdictions have increased zoning capacity in single-family residential areas.[xxv] IHOs remain the primary tool for local governments to address affordable housing needs as elected officials resist increasing zoned capacity, finding IHOs more politically palatable. Despite the pressing need, reforms to increase zoning capacity in single-family-only areas remain political kryptonite. While IHOs offer a safer political route for addressing the affordable housing crisis, they often exacerbate the high cost of housing.[xxvi]

To complicate matters, the psychology behind IHOs is problematic. By casting market-rate housing as a negative externality, a burden on communities that must be offset by taxation, developers and the homes they build—the very homes we desperately need—are met with suspicion and opposition. IHOs by default portray market-rate developments as adversaries of affordable housing, necessitating taxation to mitigate their supposed negative impacts. This is perplexing, as the root cause of housing unaffordability is the acute housing unit shortfall - primarily driven by local government zoning conditions which restrict the most affordable housing unit types to a de minimis percentage of its residentially zoned land.

The question must be posed; Why is it a surprise that the cost of both market and affordable housing development is increasing when the most affordable housing types are allowed on just 23% of residentially zoned land, all while taxes and direct costs on new home development are increasing?

Furthermore, targeting market rate housing to promote the development of affordable housing via taxation, rather than focusing on increasing zoned capacity and reducing permitting times, perpetuates the misguided notion that developers are adversaries, fostering a climate of suspicion, contempt, and resistance.[xxvii] This often leads to litigation, further inflating housing costs by making it a rare commodity. Such a contentious atmosphere now ensnares even those elected officials who support development, subjecting them to threats, recalls, and legal challenges. This vicious cycle of resistance and litigation stifles progress in addressing the true needs of housing affordability.

The essential policy question that is not being asked is whether IHOs help or hinder the development of housing at the scale required to meet demand and provide affordability. Are IHOs actually obstructing more effective policy interventions, such as increasing zoning capacity, by-right rules and fast-track approval processes?

Based on outcomes in Denver and other cities like Minneapolis, which have seen a reduction of multifamily permits, following the implementation of their IHO policy, IHOs are falling short of facilitating a regulatory environment that allows local governments to achieve their intended housing affordability goals.[xxviii] While Minneapolis is leading the way in increasing their zoned capacity, their IHO program has produced few affordable housing units and reduced the number of market rate development permits. These policies also discourage developers from creating housing that triggers IHOs, thus suppressing the very types of housing and revenue streams that IHOs aim to generate. Alas, even when local governments significantly increase their zoned capacity, the misguided notion of taxing market rate housing to fund affordable housing persists. Is it any surprise that the cost per unit of both housing types are at the highest they have been and continues to rise year over year?

Key Recommendations

Reevaluate Expanding Housing Affordability: In light of the significant decline in housing permits following the implementation of Denver's EHA ordinance, a comprehensive review of the ordinance is warranted. While the intent of the EHA is to facilitate the development of affordable housing, the evidence suggests it may inadvertently be hindering Denver's capacity to meet housing demands, counterproductively restricting supply. Denver leaders should consider eliminating or adjusting EHA to facilitate rather than hinder housing development, potentially by modifying fee structures or offering more flexible compliance options.

Significantly Increase Zoned Capacity: Denver currently lacks the zoned capacity necessary to foster a regulatory environment that supports the most affordable housing types and supply. To address this, it is essential that Denver increases the percentage of land zoned for multifamily developments. Additionally, there must be a significant reduction in barriers to the construction of duplexes, triplexes, and quadplexes, often referred to as the “missing middle” or “light touch density” especially in areas currently zoned exclusively for single-family homes.

Radically Accelerate Permit Processes: The efficiency of Denver's permitting process is paramount to keeping pace with the urgent needs of Denver’s housing market. Inspired by the successful fast-track permitting initiatives in San Diego and Los Angeles, Denver should adopt similar measures to streamline and expedite its permitting processes to include market rate housing. This approach will reduce developmental costs and timelines, allowing for greater financial feasibility of projects during this high cost of capital market environment. This will thereby encourage more developers, across all housing types, be they affordable, middle and market rate to invest in Denver, creating greater supply on an annual basis.

Going Forward

Denver’s inclusionary housing ordinance, Expanding Housing Affordability, is limiting new permits by one-third, equating to roughly 2,890 to 3,180 fewer units a year. This is pushing Denver below the number of units needed to close its supply gap and meet projected population growth. This decline persists despite the genuine commitment of Denver’s leadership, across multiple administrations, to facilitate affordable housing development.

The critical question remains: Why does Denver continue to be so costly to call home, with so many unable to afford a home at all?

Inclusionary Housing Ordinances were once seen as the optimal solution for housing vulnerable citizens—a market-based intervention promising mixed-income communities free of economic segregation. Unfortunately, data is showing large unintended consequences. At best, IHOs produce few new affordable units compared to other policy interventions like increased zoning capacity and fast-track permit approvals.

As currently constituted, and as the key component of Denver’s land use regulations and affordable housing strategy, the city’s IHO may be inadvertently perpetuating the segregated socioeconomic nature of Denver’s built environment, one that harms low income Denverites who have few other options to call home outside of the 23% of land mass more affordable housing options are relegated to.

Herein lies the dilemma: single-family zoned communities fiercely resist upzoning efforts, often resorting to litigation to block these laws. This resistance has been recently observed in Montana and Austin, where upzoning initiatives were overturned.[xxix][xxx] In Minneapolis, the courts initially halted Plan 2040, but it was ultimately upheld on appeal. Ft. Collins, which saw two upzoning attempts fail via citizen-led pressures, passed a condensed version in March of 2024.[xxxi] Despite this resistance, 63% of Denver residents support allowing duplexes and triplexes in residential neighborhoods, according to Zillow polling.[xxxii]

Denver’s leadership may be anticipating the state legislature will mandate light-touch, missing middle density reforms, such as allowing duplexes and triplexes in residential zones. However, this is a significant gamble. While the general assembly has recognized housing as a statewide concern in relation to ADUs, parking minimums, and transit-oriented upzoning, the missing middle component of SB23-213 failed and did not return in the latest assembly.[xxxiii] It remains uncertain if the legislature will take this step and hope is not a strategy. The pressing question for Denver’s leaders is, why wait?

As Denver prepares to ask constituents this November to fund affordable housing development through a 0.5% sales and use tax under the “Affordable Denver,” initiative, the city aims to raise $100 million to create 44,000 units over the next decade.[xxxiv] However, while Denver continues to tax its residents in pursuit of these goals, the city’s leadership seems to lack a parallel focus on increasing zoned capacity, a critical component of addressing the housing shortage and the resulting socioeconomic segregation impacting low income Denverites. While the administration of these funds remains unclear, should it pass, Denver should look to the innovative Montgomery Housing Opportunity Commission Loan Fund as an allocation model, which leverages $100 million to create 6,000 units without relying on scarce subsidies like Low Income Housing Tax Credits.[xxxv]

Denver stands at a pivotal moment in shaping its housing affordability future. With over $150 million already allocated from existing property and sales taxes for homelessness and linkage fees, and the potential to add $100 million more, Denver could possess financial resources unmatched by other Colorado cities. Yet, financing affordable housing remains a formidable challenge, especially as the era of cheap money has ended. In this stark light, can Denver continue to afford to utilize only 23% of its residential zoned capacity for affordable and attainable housing development? What benefit will additional revenue deliver other than escalate per-unit housing costs as home builders, both affordable and market rate compete for the same scarce, and thus incrementally more expensive, multifamily zoned land?

It's time to empower both market-rate and affordable housing developers—each essential to our housing continuum—to build the housing abundance Denver desperately needs. This requires revising zoning regulations to permit the most affordable housing types currently constrained to a minimal percentage of the city. Moreover, taxpayer funds should be invested in creating deeply affordable, mixed-income communities located near desirable amenities, rather than relegating developments to high-frequency arterials often situated in food deserts, near underperforming schools at risk of closure and costly, unreliable mass transit.

Denver must increase zoned capacity and fast-track permit approvals with the same urgency that has been applied to addressing unsheltered homelessness, during the first year of the mayor's administration.[xxxvi] If retaining the Expanding Housing Affordability Ordinance is deemed necessary, then it must be balanced by materially increasing desegregated zoned capacity and committing to approving housing permits in 60 days or less. If San Diego can achieve permit approvals in as little as 30 days—or even 9 days—so can Denver.

Appendix

Figure 10 – Sample Project Finacials in Denver vs Aurora

Difference-in-Difference Analysis

To evaluate the scale of the impact of Denver’s inclusionary housing ordinance, two statistical models were developed, both utilizing a difference-in-difference method. This is a method to estimate the impact of new policy. Specifically, it compares the data of a test or treatment group to a control group. The tables below show the statistical results from the two models. Figure 11 shows the results from performing a difference-in-difference regression analysis on the 6-month rolling average housing permitting data from the cities of Denver and Aurora, Colorado. Figure 12 shows the results from a similar analysis between Denver and the cities of Salt Lake City, Utah and Boise, Idaho. Both models show that there was a statistically significant change in the number of permits being issued in Denver(treatment group) with the other cities.

Figure 11 – Difference-in-Difference Regression Results: Denver Comparison to Aurora, 2014-2024.

Figure 12 – Difference-in-Difference Regression Results: Denver Comparison to Boise and Salt Lake City, 2014-2024.

[i] https://commonsenseinstituteco.org/colorado-housing-affordability-report/

[ii] https://www.nemours.org/content/dam/nemours/shared/collateral/policy-briefs/housing-on-child-health-brief.pdf

[iii] https://www.denvergov.org/Government/Agencies-Departments-Offices/Agencies-Departments-Offices-Directory/Community-Planning-and-Development/Denver-Zoning-Code/Text-Amendments/Affordable-Housing-Project

[iv] https://www.fanniemae.com/research-and-insights/perspectives/us-housing-shortage

[v] https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/three-reasons-we-still-build-its-1900

[vi] https://www.denvergov.org/content/dam/denvergov/Portals/646/documents/Zoning/text_amendments/Group_Living/Group_Living_Zoning_History_Equity.pdf

[vii] https://missingmiddlehousing.com/about/how-to-enable

[viii] https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/housing-abundance-with-light-touch-density/

[ix] https://www.denvergov.org/Government/Agencies-Departments-Offices/Agencies-Departments-Offices-Directory/Department-of-Housing-Stability/Partner-Resources/Dedicated-Affordable-Housing-Fund

[x] https://www.denvergov.org/Government/Agencies-Departments-Offices/Agencies-Departments-Offices-Directory/Department-of-Housing-Stability/News/Measure-2B-Addendum-to-2021-Action-Plan-Open-for-Public-Comment?lang_update=638569705165129511

[xi] https://nhc.org/policy-guide/expedited-permitting-and-review-the-basics/expedited-permitting-and-review-policies-encourage-affordable-development/

[xii] https://www.biaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Cost-of-Permitting-Delays-November-2022.pdf

[xiii] https://app.powerbigov.us/view?r=eyJrIjoiM2I1NTE3MWQtZjQ1NS00ZjRkLTk0NDItZDQwMTc5MDk3MzhmIiwidCI6IjM5Yzg3YWIzLTY2MTItNDJjMC05NjIwLWE2OTZkMTJkZjgwMyJ9&pageName=ReportSectionb1df011095bb068a0dc6

[xiv] https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/CPD/documents/PROHousingProfiles_Denver_CO.pdf

[xv] https://www.denverpost.com/2024/07/19/denver-construction-permit-wait-times-residential-mike-johnston/?utm_medium=browser_notifications&utm_source=pushly&utm_content=33%25%20cut%20in%20review%20times&utm_campaign=www.denverpost.com-5084014

[xvi] https://www.sandiego.gov/sites/default/files/executive-order-2023-1.pdf

[xvii] https://www.sandiego.gov/development-services/forms-publications/information-bulletins/195

[xviii] https://www.sandiego.gov/development-services/permits/building-permit

[xix] https://www.sandiego.gov/mayor/complete-communities-now

[xx] https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/SAND706BPPRIV

[xxi] https://mayor.lacity.gov/news/mayor-bass-signs-executive-directive-dramatically-accelerate-and-lower-cost-affordable-housing

[xxii] https://www.denvergov.org/Government/Agencies-Departments-Offices/Agencies-Departments-Offices-Directory/Community-Planning-and-Development/Plan-Review-Permits-and-Inspections/Development-Fees

[xxiii] https://denvergov.org/files/assets/public/v/2/community-planning-and-development/documents/zoning/text-amendments/housing-affordability/eha_legislative_reviewdraft_summary_march2022.pdf

[xxiv] https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/working-papers/inclusionary-housing-in-united-states/

[xxv] https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/articles/2022-12-state-by-state-guide-to-zoning-reform/

[xxvi] https://manhattan.institute/article/the-exclusionary-effects-of-inclusionary-zoning-economic-theory-and-empirical-research

[xxvii] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/29/upshot/developer-dirty-word-housing-shortage.html

[xxviii] https://www.startribune.com/report-on-minneapolis-inclusionary-zoning-policy-sees-decrease-in-large-apartment-projects/600197302/

[xxix] https://www.kut.org/austin/2022-03-17/austin-city-council-codenext-zoning-plan-violated-texas-law

[xxx] https://montanafreepress.org/2024/01/02/bozeman-judge-blocks-two-pro-construction-housing-laws/

[xxxi] https://www.fcgov.com/planning-development-services/luc

[xxxii] https://www.zillow.com/research/modest-densification-zhar-30934/

[xxxiii] https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/sb23-213

[xxxiv] https://www.denverpost.com/2024/07/08/denver-mike-johnston-sales-tax-increase-afforable-housing-election/

[xxxv] https://www.hocmc.org/extra/1115-housing-production-fund.html

[xxxvi] https://denvergov.org/files/assets/public/v/1/mayor/documents/programs-amp-initiatives/homelessness/aimh-report.pdf