Introduction

Colorado’s education funding system is broken in several ways: inequitable revenue collection, an inefficient and outdated allocation formula, and a retirement system that costs the state nearly a billion dollars annually just to pay down the $30 billion in unfunded liability. HB21-1164 helps the system start on a path of correction by addressing the patchwork system of property taxes on the revenue side. The extra revenue raised by this bill could help alleviate some of the budgetary pressures on K-12 education. The bill does not, however, address the flawed funding formula on the distribution side of the equation, and there are legitimate concerns that the bill violates the constitution by increasing taxes without a vote.

The current education funding system is laden with problems and inefficiencies that hinder schools from functioning at their highest levels. Increasing revenues without addressing the severe flaws in how the state allocates those revenues, as HB21-1164 does, is a missed opportunity to improve student outcomes.

Background

The Revenue Problem

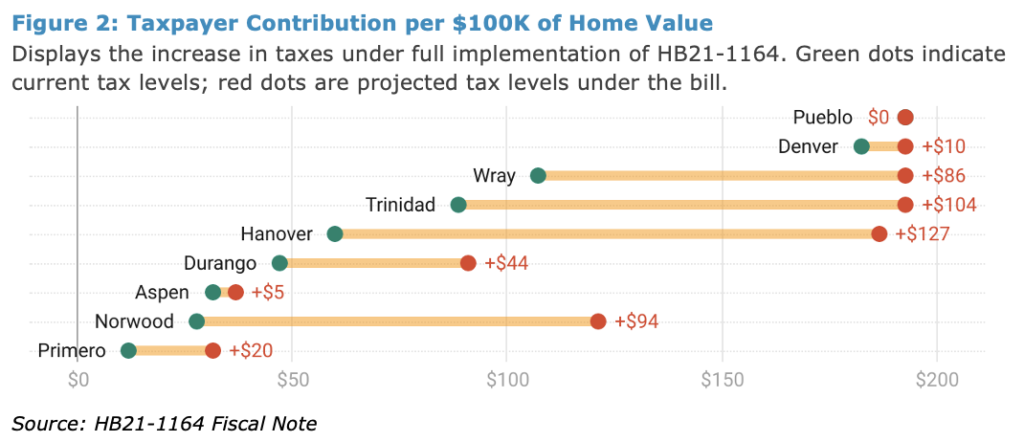

The school finance act requires local revenues be used to fund public education before the state contributes any dollars. The legislature first calculates the local share, derived from property taxes and specific ownership taxes, and if the local share is short of what the district needs to fund its schools, then the state is obligated to fill the remaining amount. The problem is that the way property taxes for K-12 are collected is inequitable and results in homeowners across the state contributing vastly differing amounts on the same amount of home value (see Figure 2 on page 3).

Between 1993 and 2007, districts were required by the Colorado Department of Education to reduce property tax rates as assessed property valuations increased, even if voters had already “de-Bruced,” or approved that the school district could keep revenues above the TABOR limit. Now, some districts, such as Aspen, levy 4.4 mills for K-12 education, while districts such as Pueblo City levy 27 mills (the maximum allowed). Because of Aspen’s high property wealth, the district’s 4.4 mills bring in a substantial amount of local funding, but the local revenue is still short of what is needed to fund schools under the School Finance Act formula. Thus, Aspen continues to be subsidized by the state, which takes away dollars that could go to less wealthy districts and students who need additional support. The inequitable revenue system means the amount of tax effort being put forth by residents in some areas such as Aspen is much lower than the tax effort of residents in Pueblo, Denver and other districts.

The Formula Problem

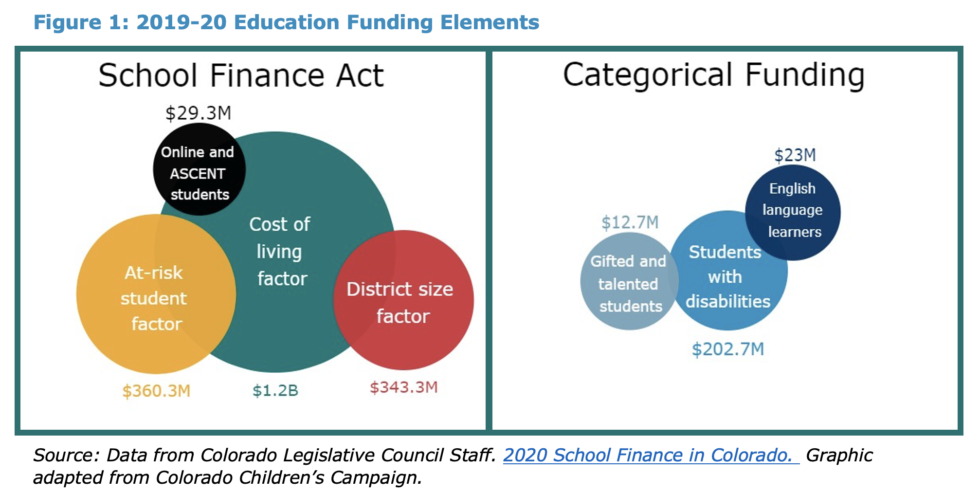

The state determines how much money each school district needs through an outdated formula that favors districts factors (district size; cost of living) over student needs (e.g. students with disabilities, English language learners, and gifted and talented students). Districts receive categorical funding to support students with different needs, but that funding does not come through the School Finance Act formula leading to inefficient allocations and amounts that pale in comparison to the cost-of-living factor (see Figure 1). While the funding formula does allocate funding to support “at-risk” students, the calculation for doing so is flawed and provides an incomplete picture of poverty levels. The result is that some districts with high costs of living receive more state dollars on a per pupil basis than districts with more students in poverty.

HB21-1164 Overview

HB21-1164 attempts to remedy the inequitable local revenue landscape.

Under HB21-1164, the state will no longer subsidize artificially low total mill levies by increasing the local share contribution of some districts to be on par with other communities. School districts would be on a more level playing field in terms of K-12 property taxes.

The remedy may not be constitutional.

The bill proposes to do this by arguing that, in essence, the Colorado Department of Education incorrectly reduced property taxes rates for school districts that had de-Bruced. The bill resets the mills to the lesser of the level the school district was at when it de-Bruced, the level needed to be fully funded locally, or, 27 mills. The legislature has asked the Colorado Supreme Court to issue a judgement about whether such action is legal. If the court rules that it is legal, the legislation is expected to be sent to the governor’s desk.

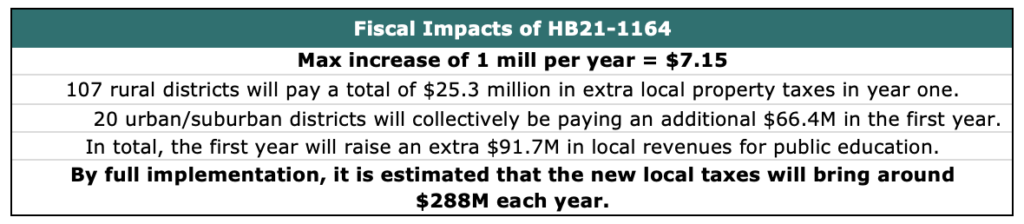

The remedy is not cheap.

While the bill does help address local revenue inequities, it comes at a cost. The average increase in mills under HB21-1164 is 4.2 mills. 17 school districts (all rural) will see an increase of 10 to 18 mills, which will be phased in over time as the bill limits the tax increase to no more than 1 mill per year.

Figure 2 highlights the impact HB21-1164 will have on taxpayers in select districts. The increase in mill levies is substantial for many districts; 125 of 178 districts will end up at 27 mills, up from only 39 districts currently. There will still be somewhat uneven local contributions to public education because several districts had locked in lower mill levies when they de-Bruced, and other districts can be locally funded at lower mill levels.

HB21-1164 does not propose any changes to the school finance formula that allocates funding to districts.

By increasing local revenues, the bill frees up the same amount in state dollars. The additional $288 million in local revenue means that state will have $288 million of state dollars freed up. HB21-1164 requires that Colorado allocate those savings back to education, but it is not clear how those dollars will be spent.

If this significant amount of extra revenue for education is funneled through the same outdated, inequitable formula, it is unlikely we will see improved outcomes for students.

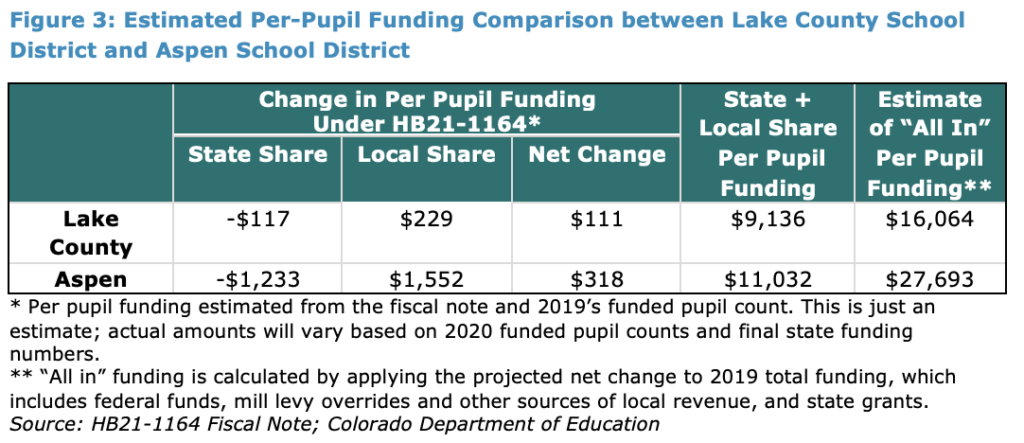

Policymakers should consider proposing changes to the school finance formula that allocates funding more equitably to districts if HB21-1164 is found to be constitutional. Figure 3 provides an example of inequitable funding levels between two districts, which will not fundamentally change under this legislation unless the funding formula and other systemic issues are addressed.

Under HB21-1164, the local share increases and the state share decreases for both Aspen and Lake County. According to the fiscal note, in in the first year of implementation of the bill, Aspen will be fully funded locally and will not need to be subsidized by the state. Given their high property wealth and low mill rate, this shift makes common sense.

Lake County, which serves a more diverse population with less wealth than Aspen, sees a smaller net increase in funding in the first year of implementation and the district’s per pupil funding remains more than $11,000 below that of Aspen. Without addressing the school funding formula, the overall funding levels of Aspen and Lake County do not significantly change.

In the long term, as the reset mill levies generate additional revenue, the state will have the opportunity to use the $288 million a year to target funding to districts such as Lake County that have lower property wealth and higher student need. Funneling the additional revenue through the current funding formula, however, does not meaningfully change anything for students.

Lastly, the legislation does not address the local revenues collected for education through mill levy overrides.

When CDE directed districts to ratchet down property taxes to remain below the TABOR revenue limit, local revenue declined, and the state was unable to make up for the decrease. This led many communities to vote to increase property taxes through mill levy overrides. Some communities have not been successful at getting voter approval for an override, adding to the layers of complexity and inequity in our education finance system. Nonetheless, many taxpayers are contributing a significant amount of property taxes toward K-12 education through override mills, which total $1.4 billion a year. Under the current version of this bill, taxpayers do not get credit for those tax payments.

For example, Wray School District currently levies 15 mills for its schools, and the district is required by this bill to levy an additional 12 mills. But, over the past several years, taxpayers in Wray have already approved 13 override mills to support their schools. The district is not able to apply the override mills to fulfill their local revenue obligation under this bill. Instead, after full implementation, Wray will be levying 40 mills for public education, despite the intent of the bill to get most districts to a level playing field of 27 mills.

Key Takeaways

- HB21-1164 increases local property taxes for K-12 education by $91.7 million in the first year and by an estimated $288 million in full implementation. The Colorado Supreme Court is deciding whether the bill is constitutional.

- The current funding system has several serious flaws to its structure and increasing revenues without addressing those flaws, as HB21-1164 does, is a missed opportunity to create a system that works effectively for students.

- The outdated education funding formula does not meet the diverse needs of today’s students, and it places undue weight on district characteristics.

- If this bill is enacted, policymakers will need to consider how to spend the $288 million in new education revenue in way that meets individual student needs and further reduces funding inequities.