During the 2021 legislative session, Colorado lawmakers may reconsider a proposal to create a state-controlled health care plan commonly called “the public option.” An earlier attempt to pass the public option stalled in 2020, amid the economic fallout of COVID-19 lockdown measures and the severe strain of the pandemic on Colorado’s health care system.

In this report, some of the lessons learned from the public option debate thus far are reviewed. Common Sense Institute has been deeply involved in this debate, producing three separate studies on the subject between September 2019 and May 2020. This report details five issues that lawmakers should consider if legislation to create a Colorado public option is reintroduced this year.

In short, even before COVID-19 took a massive toll on the state’s health care system, there was significant concern about cutting hospital budgets or further increasing private insurance costs in order to pay for the public option. After a full year of pandemic-level conditions across the state’s health care system, those concerns have escalated. At the same time, there is also new information that calls into question some of the central assumptions made by public option advocates in support of creating a new state-controlled health plan.

Calling into question some of the most impactful components of the public option debate, does not mean that no problems exist. It should only reinforce the need to improve regulation surrounding health care markets, which can achieve shared goals of slowing consumer prices while mitigating the unintended consequences of newly intrusive legislation. These new factors in the debate, which are critically important, will now be addressed in more detail.

- CSI published a study on HB 20-1349 in May 2020, which found significant financial ramifications from the proposed Colorado Option, due to its reliance on government-set prices and required participation by hospitals and insurance carriers.[i] This study was based on a model calibrated specifically for Colorado and the design of the Colorado Option Plan in HB 20-1349.

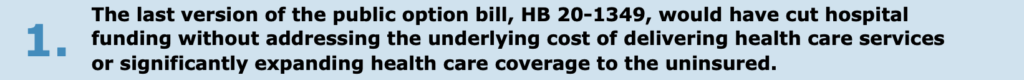

- The study found hospitals would face annual revenue cuts starting at $536 million growing to $1.1 billion within the Colorado Option’s first three years. Approximately 4,800 health care workers could lose their jobs – the equivalent of 7% of all hospital sector jobs in Colorado.

- Rural hospital revenue losses under the Colorado Option could exceed 6%, which is more than double the loss of revenue for hospitals in urban areas of the state.

- The Colorado Option would force hospitals to make a critical choice: Cut services and access to care or pass the costs of the state-controlled plan to the majority of Coloradans who are covered through private health plans.

- Shifting the unpaid costs of the Colorado Option to private health plans would impose additional costs on employers and workers, creating a drag on the economy that results in a net loss of 6,400 jobs and $619 million per year in personal income.

- If cost shifting does not occur, then hospitals may be forced to reduce critical services or reduce access. A 2020 study performed by FTI Consulting indicated major budget challenges under a Colorado public option, even during pre-pandemic conditions. The FTI study concluded 83% of hospitals would experience revenue losses due to the public option, “threatening access to care disproportionately in certain areas of the state where hospitals are already operating in tight margins.”[ii]

- Despite these costs, the state-controlled plan would only attract 18,000 people – or 5.3% – from the ranks of Colorado’s uninsured. Almost 90% of participants in the Colorado Option, therefore, would migrate from existing private health plans into the government-sponsored plan.

- CSI’s May 2020 study was the third in a series on proposals for a state-level public option in Colorado. Overall, our research on these proposals has found that reducing the amount that hospitals are paid to treat patients does not change the costs that are incurred in the course of treating those patients. The unpaid costs of the public option do not simply disappear. Instead, those unpaid costs are shifted somewhere else, where they can cause major damage to our health care workforce, to the markets where most people obtain health care coverage, and to businesses and households across the economy.

- While the existing health care marketplace is distorted because of the growing scale of public payers and regulations unique to health care, the introduction of a public option payer would only further distort the marketplace. By delivering limited savings to a small share of Coloradans, it would only increase costs on remaining commercial insurance, or further stress hospitals’ ability to provide certain services.

- Prior versions of the public option, at the state and federal level, have all used government rate setting to cut payments to hospitals and other health care providers. Much like rent control in the residential housing market, this distortion only benefits a small number of consumers, while inflicting further harm on all other stakeholders.

- Recent estimates from the Colorado Hospital Association (CHA) show an immediate $4.6 billion to $7.1 billion loss from COVID-19, due to a range of factors including: Higher pandemic-related expenses for personal protective equipment, medical supplies and additional critical care beds to treat the influx of COVID-19 patients; the suspension of non-emergency medical procedures; patient avoidance of hospital care; reduced travel and tourism into the state; and state budget cuts to hospitals due to the steep decline in the economy and associated tax revenues.[iii]

- Even after emergency financial aid from the federal government and other efforts to mitigate these impacts, net losses for Colorado hospitals due to COVID-19 are still anticipated in the range of $2 billion to $4.4 billion. CHA projections also show 2021 is likely to be worse than 2020. On a percentage basis, an 8% revenue shortfall was expected by the end of 2020, with losses deepening to 11% during 2021.

- The introduction of a state-level public option over the next few years would hit hospitals while they are still recovering from the budget crisis triggered by COVID-19. Large revenue losses brought on by the pandemic have stressed the budgets of many hospitals and introduction of a public option would only add to that stress.

- The 2020 FTI study further projected up to 23 rural hospitals in Colorado “could be at increased risk of closure under the proposal as a result of reduced reimbursements.” This is consistent with another key finding from CSI’s May 2020 study on the public option: Colorado’s rural hospitals would face nearly twice the relative magnitude of financial impacts as urban hospitals on a percentage basis.

- The financial stability of rural hospitals is especially critical because other health care providers are in short supply in many rural communities. For example, December 2020 data the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services shows more than 1.1 million Coloradans live in a designated Health Professional Shortage Area.[iv] The same data shows an increase of 258 primary health care providers is needed to overcome the shortage in rural Colorado.

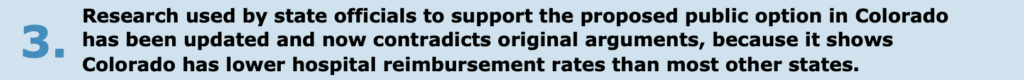

- Before the introduction of HB 20-1349, the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy (HCPF) and Financing and the Colorado Division of Insurance (DOI) published a report making the case for a state-level public option.[v] This report, requested by the legislature during the 2019 session, relied on research conducted by the RAND Corporation into hospital reimbursement rates in Colorado and other states.[vi]

- The updated analysis puts Colorado in the bottom half of RAND’s measurement of hospital prices nationally and contradicts the original rationale provided in the HCPF-DOI report in support of the Colorado Option.[vii] Again, this does not mean there is not a problem, however supporters of the public option should be more precise in the assessment of both the extent of the problem and the impacts of any remedy.

- Public option supporters in Colorado are following the lead of Washington state, where the state-controlled insurance plan is known as Cascade Care. However, public-option plans for 2021 – the first year of coverage under Cascade Care – have not delivered the savings proponents anticipated.

- Public option plans cost up to 29% more than traditional private health plans on Washington state’s individual health insurance market, according to data from the Washington Health Benefit Exchange. Analysis of the data by Bloomberg Law further concluded: “Washington state’s first-in-the-nation program is resulting in higher premiums than private-sector plans in many instances, the opposite of what was forecast about a ‘public option’ by proponents.”[viii]

- A separate analysis by the Public Option Institute and Wynne Health Group noted significant regional differences in Cascade Care premiums, concluding: “In general, it appears that public option plans will provide the most cost relief in counties where competition is currently limited and where, perhaps as a result, premium prices are higher.”[ix]

- This likely means Washington state’s public option was more expensive in urban areas, which have more competition, and less expensive in rural markets, which have less competition. An unintended consequence of this trend, however, could be concentrating hospital revenue losses in rural communities and exacerbating already existing disparities in access to health care between urban and rural communities.

- The first year of Cascade Care also demonstrated the financial pressures created by government rate-setting. After capping reimbursement rates, Washington state allowed insurers and healthcare providers to determine whether they could participate in the public option in a financially viable manner. However, only 5 of the state’s 13 insurance carriers elected to participate, and as a result, the public option was only offered in 20 of the state’s 39 counties.[x] This example may hold important lessons for Colorado lawmakers in terms of understanding the financial stresses associated with a public option, especially if participation in the public option is mandated.

The public option initially targets the individual or non-group health insurance market, where approximately 7% of Coloradans get their health care coverage, according to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). However, public option proponents have indicated interest to expand the public option plan into small and even large group markets in the future.

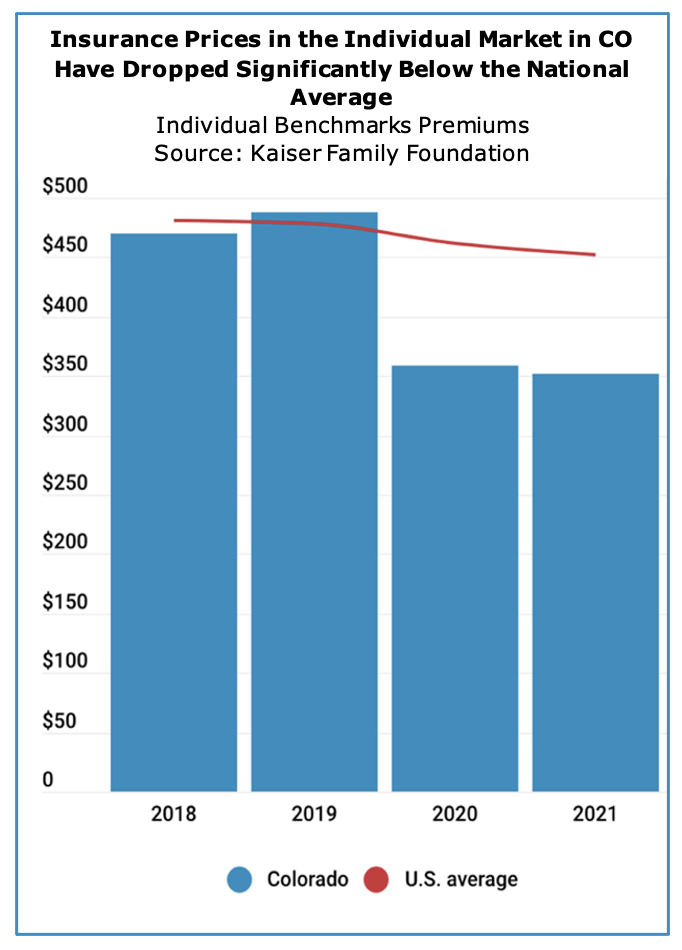

The public option initially targets the individual or non-group health insurance market, where approximately 7% of Coloradans get their health care coverage, according to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). However, public option proponents have indicated interest to expand the public option plan into small and even large group markets in the future.- KFF data also shows average benchmark premiums for individual health plans in Colorado have fallen by 28% since 2019.[xi] For tracking purposes, KFF defines the benchmark premium as the second-lowest cost silver premium for a 40-year-old. This key metric is used to track the overall movement in premiums for all households that obtain health coverage in the individual market.

- The 28% decline since 2019 means Colorado now has the 6th least expensive average benchmark premiums in the country. At $351 per month, Colorado’s benchmark premium in 2021 is also 22% lower than the national average of $452 per month.

- State officials have credited Colorado’s new reinsurance program for helping to lower average individual health insurance premiums.[xii] Under the reinsurance program, which was created by the state legislature in 2019, the State of Colorado helps insurance companies cover the cost of their most expensive claims, which then allows lower premiums to be offered to other consumers in the individual health insurance market. The reinsurance program’s first year of implementation was 2020, so it has only been in effect for two enrollment periods.

- The state legislature and the Polis administration began pushing for a public option in Colorado in 2019. At that point, Colorado’s benchmark premiums were 2% above the national average and ranked as the 27th least expensive (or 25th most expensive) across all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The current trends in Colorado’s individual health insurance market are dramatically different than they were in 2019, calling into question the assumptions and arguments made by public-option advocates in support of the creation of a new state-controlled health plan.

[i] Common Sense Institute: The Colorado Option Plan: Modeling the Impacts of Government Price Controls in Health Care, May 7, 2020: https://commonsenseinstituteco.org/co-option-plan/

[ii] FTI Consulting: The Colorado State Government Option: Assessing the Impact of Proposed Reforms

on Access to Health Care, January 2020: https://www.fticonsulting.com/~/media/Files/us-files/insights/reports/2020/jan/colorado-government-option-assessing-reforms-health-care.pdf

[iii] Colorado Hospital Association: COVID Hospital Financial Impact & Federal Relief, October 2020

[iv] U.S. Department of Health & Human Services: First Quarter of Fiscal Year 2021 Designated HPSA

Quarterly Summary, December 31, 2020: https://data.hrsa.gov/Default/GenerateHPSAQuarterlyReport

[v] Colorado Division of Insurance and Colorado Department of Health Care Policy & Financing: Final

Report for Colorado’s Public Option, November 15, 2019: https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/Final%20Report%20for%20Colorados%20Public%20Option.pdf

[vi] https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3033.html

[vii] https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR4394.html

[viii] Bloomberg Law: First Government-Run Health Plan Portends Rocky Start for Biden, Nov. 18, 2020:

https://news.bloomberglaw.com/health-law-and-business/public-option-health-plan-in-washington-state-a-caution-to-biden

[ix] Public Option Institute and Wynne Health Group: Payor Participation in Washington’s Public Option

Plan and Impact on Premiums: https://www.publicoptioninstitute.org/feed-wa-implementation-materials/payor-participation-in-washingtons-public-option-plan-and-impact-on-premiums

[x] Washington State Health Care Authority: HCA finalizes contracts with five carriers for Cascade Care,

October 8, 2020: https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/WAHCA/bulletins/2a4f2fb

[xi] Kaiser Family Foundation: Marketplace Average Benchmark Premiums, 2014-2021:

https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/marketplace-average-benchmark-premiums/

[xii] Colorado Division of Insurance: Reinsurance Keeps Premiums Down for 2021, July 29, 2020:

https://doi.colorado.gov/press-release/reinsurance-keeps-premiums-down-for-2021